James I of Aragon (appropriately known as James the Conqueror) landed at Santa Ponça, Majorca on this day in 1229—launching the first of his campaigns to capture the Balearic Islands.

The largest of the islands, Majorca lies at the heart of economic and cultural interchanges in the Mediterranean. Its geographic location made it highly coveted among medieval rulers in the region.

How did rulers envision their territory during the medieval period? More broadly, how did inhabitants of the medieval world perceive their place? During this time, maps are rare and typically utilitarian—the scarcity attributed to the exhaustive efforts to produce them. Mappae mundi (“maps of the world”) are the earliest forms of maps. From these, we glimpse into the unique role map-making has in science and art. Maps document what we know about the space we live in (that is the science, or “knowledge”), but also what that that space means to us (the art, or “know-how”).

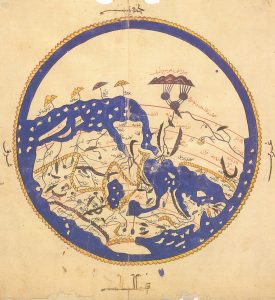

Ptolemy’s Geography introduced longitude and latitude, as well as projection. Prior to the rediscovery of Ptolemy’s work in the Renaissance, space in the world wasn’t conceptualized as calculable or geometrically divisible. Thus, mappae mundi demonstrate a linear dimension of time and space. For example, 12th century geographer Al-Idrisi of Al-Ánalus (medieval Muslim territory covering modern-day Spain and Portugal), created this mappa mundi:

The map is akin to a travel guide—noting physical barriers like mountains, available natural resources, traded commodities, and visualizing distance relative to travel time. Other mappae mundi served a different purpose. The Hereford Mappa Mundi depicts Jerusalem at the center of the world, with accompanying illustrations of religiously significant people and places. Without Ptolemy’s mathematical approach, there is no universal “center” familiar in the maps of today.