- Indigenous peoples worldwide have lived harmoniously with their natural environments for millennia, and traditional Indigenous cultures are highly intertwined with nature. As a result, many Indigenous languages have a variety of different words for weather, terrain, plants, and animals that are commonly described by only one word in the English language. Such rich terminology reflects the nuanced understanding of the complexities of the environment and climate-related phenomena by Indigenous peoples.

- The word “climate” cannot be directly translated in many Indigenous languages. The term for climate originates from Europe in the late 14th century to describe the weather characteristics of certain geographical regions.

- Indigenous languages are highly diverse, with many different dialects existing globally. For example, there are between 200 to 300 recognized Indigenous languages in Australia, and around 175 Indigenous languages are still spoken in the United States.

Australian First Nations Languages

Note: Australian First Nations people are commonly referred to as Australian Aboriginal people. However, the term aboriginal can be offensive to some Indigenous peoples as the term’s prefix “ab” can mean “not,” leading aboriginal to be directly translated as “not original.”

- Indigenous Australian languages are linguistically distinct from the rest of the world due to the Indigenous people’s geographic isolation for over 40,000 years. Within the Australian continent, hundreds of different languages developed, mainly due to population migrations and topographical boundaries (map artwork below). In densely populated areas throughout history, many Indigenous people spoke several languages and communicated across linguistic boundaries. Today, Indigenous groups in nearby locations speak similar, yet distinct dialects.

Word map artwork in the shape of the Australian continent. Each word represents the name of an Indigenous Australian group and is generally located near their traditional land (from Burdon, 2016).

- Below is a table of translations for four climate-related words (hot weather, cold weather, wind, and rain) in various Australian Indigenous languages. Notice the number of Indigenous languages spoken across Australia and the differences in words with the same meaning across dialects.

Climate-Related Australian First Nations Vocabulary Table

| Language | Hot Weather | Cold Weather | Wind | Rain |

| Yinhawangka | Buyungkaji | Bulhurru | Warlba | Thurla Mindi |

| Central Anmatyerr | Utern | Alhwerrp | Rlkang | Kwaty |

| Ngalia | Kurli Kampara | Wanta | Pirriya | Yiili |

| MalakMalak | Lerrpma | Kerrgetjma | Perrperrma | Mada |

| Matuharra | Unurn | Pirriya | Warlpa | Kapi |

| Kukatja | Yupunytju | Garrigal | Mayawun | Kalyu |

| Bangerang | Datjidja | Bolkatj | Banga | Gorrkarra |

| Bunganditj | Wuwat Karu | Mut-mut Karu | Niritja | Kabayn |

| Ngaanyatjarra | Kurli | Warri | Pirriya | Kapi |

| Djinang | Warlirr | Mirn | Warti | Mayurrk |

| Bunuba | Jambarla | Ngirrilya | Giwa | Gawa |

| Barngarla | Boogara | Bai Ala | Warri | Gadari |

| Manyjilyjarra | Puyurlurru | Wantajarra | Nyarta | Kapikalyu |

| Nbjébbana | Wárlirr | Ngarídda | Balawúrrwurr | Malóya |

| Gunditjmara | Kaloyn | Palapitj | Ngurnduk | Mayang |

| Kuninjku | Nga-Ladminj | Nga-Bonjdjek | Kun-kurra | Man-djewk |

| Wambaya | Gambada Linjarrgbi | Garrijarrija | Wunba | Galyurrungurna |

| Marri Ngarr | Wuyi Walngayi | Wuyi Ringi | Tje Wirrir | Wudi Djenyel |

| Palawa Kani | Lakaratu Luwara | Thiyanalapana | Tiyuratina | Mungalina |

| Mawng | Kinyjapurr | Wumulukuk | Marlu | Walmat |

| Gija | Barnden | Warn’gan | Waloorrji | Jadany |

| Warnman | Kawurr Kawurrpa | Warri | Karlalarra | Kuluwa |

| Mathi Mathi | Wathai | Minhi | Wilangi | Midaki |

| Pitjantjatjara | Kuli Pulka | Wari Pulka | Walpa | Mina |

| Tiwi | Tiyari | Yirriwinari | Wurnijaka | Pakitiringa |

| Bilinarra | Barunga | Magurru | Burriyib | Yibu |

| Dalabon | Warlirr | Yekku | Kurra | Djewk |

| Wiradjuri | Yiraybang | Makurra | Giray | – |

| Gumbaynggirr | Wiijum | Niirum-Niirum | Gurriin | Guluun |

| Djambarrpuynu | Gorrmur | Guyinarr | Wata | Walktjan |

From Research Unit for Indigenous Language

Note: Pronunciation guide for Australian First Nation dialects is listed at the bottom of the page.

The North American Lunar Calendar and Climate

- Indigenous peoples native to North America usually follow a twelve to thirteen-month calendar based on lunar cycles. These lunar calendars are tied culturally and linguistically to changing natural cycles. Since each month coincides with a revolution of the moon around the Earth, Indigenous groups referred to them as ‘moons.’ Many Native American calendars started the year in the spring, a period of rebirth and the return of plant and animal life. Different Indigenous groups had different names for each lunar month, often related to important natural cycles pertinent to the group’s livelihood and sustenance. For example, moons are named after that time period’s relation with crop harvests or animal behavior. The differences between moon names give insight into the differences in climate and phenology, natural cycles affected by seasons, between North American regions.

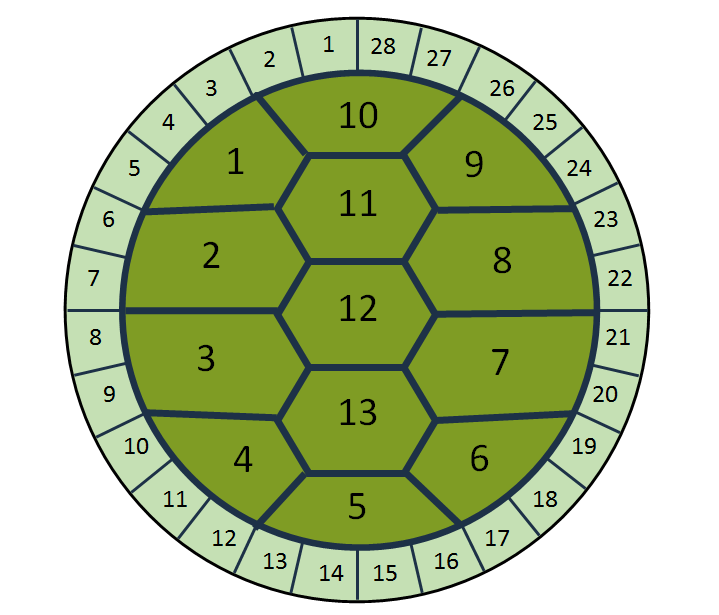

- Many First Nations in Canada have calendars that follow a thirteen-month lunar calendar, often represented by the shell pattern on a turtle’s back (image below). Each section of the turtle’s shell represents one lunar moon, with thirteen in a full year. The outer shell represents each day in a lunar month, with a total of 28 days between each full moon.

- Unlike First Nations calendars, the Gregorian calendar, used by Western society, is a solar calendar. A year has 13 lunar cycles, while the Gregorian calendar only has twelve months. Because the Gregorian calendar and Indigenous calendars, with 13 lunar months, don’t align, translations often match Indigenous moons with the Gregorian months they are most frequently associated with. Additionally, some Indigenous groups have multiple names for the lunar month, and direct translations often vary as lunar cycles can overlap in the same calendar month.

A diagram of a turtle’s shell as a lunar calendar. Each plate in the inner shell represents a lunar month. Each plate on the outer shell corresponds with a day in each lunar month, going counterclockwise (from Ontario Parks, 2010).

- Below are two tables translating the names of lunar months (moons) of four different calendars: the Abenaki, Anishinaabeg, Lakota, and Cree. Notice the natural phenomena described by the moon names in relation to the time of year. How do the names of each moon relate to the climate of the location each Indigenous group resides in? How are the seasonal conditions embodied in the translations of the different moons? Do the seasonal events indicated by the names of the moons still occur at the same time of year with ongoing climate change?

Abenaki and Anishinaabeg Lunar Month Translations

| Gregorian Month | Abenaki (Northeastern U.S.A. + Canada) | Anishinaabeg (Great Lakes, U.S.A. + Canada) | ||

| Moon | Direct Translation | Moon | Direct Translation | |

| March | Mozokas | Moose Hunting Moon | Onnabiden Giizis | Snow Crust Moon |

| April | Sogalikas | Sugar Maker Moon | Popogami Giizis | Broken Snowshoe Moon |

| May | Kikas | Field Planter Moon | Nimebine Giizis | Sucker Moon |

| June | Nakkahigas | Hoer Moon | Waabigonii Giizis | Blooming Moon |

| July | Temaskikos | Grass Cutter Moon | Miin Giizis | Berry Moon |

| August | Temezôwas | Cutter Moon | Minoomini Giizis | Wild Rice Moon |

| September | Skamonkas | Corn Maker Moon | Wabaabagaa Giizis | Changing Leaves Moon |

| October | Penibagos | Leaf Falling Moon | Binaakwe Giizi | Falling Leaves Moon |

| November | Mzatanoskas | Freezing River Moon | Baashakaakodin Giizis | Freezing Moon |

| December | Pebonkas | Winter Maker Moon | Minado Giisoonhs | Little Spirit Moon |

| January | Alamikos | Greetings Maker Moon | Minado Giizis | Spirit Moon |

| February | Piaôdagos | Falling Branch Moon | Makwa Giizis | Bear Moon |

From (Western Washington University Physics/Astronomy Department, 2022) and (“Moons of Anishinaabeg,” n.d.)

Lakota and Cree Lunar Month Translations

| Gregorian Month | Lakota (North and South Dakota, U.S.A.) | Cree (Widespread Canada) | ||

| Moon | Direct Translation | Moon | Direct Translation | |

| March | Ištáwičhayazaƞ Wí | Moon of Sore Eyes | Mikisiwipisim | Eagle Moon |

| April | Pȟeží Tȟó Wí | Moon of Green Grass | Niskipisim | Gray Goose Moon |

| May | Čhaƞwápe Tȟó Wí | Moon of Green Leaves | Athikipisim | Frog Moon |

| June | Thíƞpsiƞla Itkáȟča Wí | Moon When Turnips are in Blossom | Opiniyawiwipisim | Moon When Leaves Come Out |

| July | Čhaƞpȟá Sápa Wí | Moon when Chokecherries are Black | Opaskowipisim | Feather Molting Moon |

| August | Wasútȟuƞ Wí | Moon of Ripeness | Ohpahowipisim | Moon When Young Ducks Begin to Fly |

| September | Čhaƞwápe Ǧí Wí | Moon of Brown Leaves | Nimitahamowipisim | Snow Goose |

| October | Čhaƞwápe Kasná Wí | Moon of Falling Leaves | Pimahawmowipisim | Migrating Moon |

| November | Waníyetu Wí | Winter Moon | Kaskatinowipisim | Freeze Up Moon |

| December | Tȟahé Kapšúƞ Wí | Moon When Deer Shed Their Antlers | Thithikopiwipisim | Young Fellow Spreads the Brush Moon |

| January | Wiótheȟika Wí | Moon When the Sun is Scarce | Opawahcikanasis | Old Fellow Spreads the Brush Moon |

| February | Cȟaƞnápȟopa Wí | Moon of Popping Trees | Kisipism | Old Moon |

From (Remle, 2013) and (Western Washington University Physics/Astronomy Department, 2022)

Note: Pronunciation guide for Native American dialects is listed at the bottom of the page.

Richness of Indigenous Languages Describing Climate

- Many Indigenous languages have a rich pool of words to describe specific weather-related phenomena, especially those that shape the climate and livelihoods of Indigenous peoples.

- The Inuktitut people who reside in Eastern Canada, for instance, have at least a dozen different base words for snow and ice (table below). These base words can be expanded and combined with other descriptive words to further describe climatic conditions. Other Indigenous peoples who live in frigid northern climates have similarly comprehensive climate-related lexicons. The Iñupiaq people, who are native to Alaska, have many words for the state of ice. Today, however, some Iñupiaq elders are unable to describe the current state of melting ice caused by climate change in their native language, as it is not something that they have seen before in their lifetimes.

Inuktitut Words for Ice and Snow

| Inuktitut | English |

| Qanik | Snow falling |

| Aputi | Snow on the ground |

| Pukak | Crystalline snow on the ground |

| Aniu | Snow used to make water |

| Siku | Ice in general |

| Nilak | Freshwater ice, for drinking |

| Quinu | Slush ice by the sea |

Table of snow and ice-related Inuktitut words on the left and their English translations on the right (from “Inuktitut Words for Snow and Ice,” 2015).

Pronunciation Guides:

- “American Indian Pronunciation Guide.” Native Languages of the Americans. N.d. http://www.native-languages.org/guides.htm.

- “The Sounds and Writing Systems of Aboriginal Languages.” Education Standards Authority.2010.https://ab-ed.nesa.nsw.edu.au/go/aboriginal-languages/practical-advice/the-sounds-and-writing-systems-of-aboriginal-languages.

References and additional resources

- Burdon, A. “Speaking up.” Australian Geographic. 2016. https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/history-culture/2016/04/speaking-up-australian-aboriginal-languages/.

- “Climate (n.).” Online Etymology Dictionary. 2017. https://www.etymonline.com/word/climate.

- Cyca, M. “9 Facts About Native American Tribes.” History.com. 2022. https://www.history.com/news/Native-american-tribes-facts.

- Delaney, D. et. al. “Language, culture and environmental knowledge.” Indigenous Weather Knowledge. 2015. http://www.bom.gov.au/iwk/culture.shtml.

- Heath. J. G. “Australian Aboriginal Languages.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2017. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Australian-Aboriginal-languages.

- “Inuktitut Words for Snow and Ice.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2015. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/inuktitut-words-for-snow-and-ice.

- Lough, B. “Why the term ‘aboriginal’ has fallen out of favour in Saskatchewan.” Global News. 2016. https://globalnews.ca/news/2810963/why-the-term-aboriginal-has-fallen-out-of-favour/.

- “Native American Calendar.” Native Net. n.d. http://www.native-net.org/na/native-american-calendar.html.

- MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences. “Saving Iñupiaq: preserving a language and navigating climate change.” MIT Climate Portal. 2020. https://climate.mit.edu/posts/saving-inupiaq-preserving-language-and-navigating-climate-change.

- “Moons of Anishinaabeg.” Northern Michigan University: Center for Native American Studies. n.d. https://nmu.edu/nativeamericanstudies/moons-anishinaabeg-0.

- Ontario Parks. “The Lunar Calendar on a Turtle’s Back.” Ontario Parks Blog. 2018. https://www.ontarioparks.com/parksblog/the-lunar-calendar-on-a-turtles-back/.

- Remle, M. “Lakota (moons) Months.” LRInspire. 2013. https://lrinspire.com/2013/11/22/lakota-moons-months-by-matt-remle/.

- Research Unit for Indigenous Language. “50 Words Project.” 50 Words Project. n.d. https://50words.online/.

- “Thirteen Grandmother Moons.” Open Library Publishing Platform. n.d. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/indigstudies/chapter/13-grandmother-moons/.

- Western Washington University Physics/Astronomy Department. “Native American Moons.” Western Washington University. 2022. https://www.wwu.edu/astro101/indianmoons.shtml.