How is this related to climate?

- Volcanoes are arguably one of the most impressive and impactful natural phenomena commonly portrayed in various forms of art, across the world and throughout history. They can have effects on local and global climate long after the eruption is over, so many volcano-inspired works of art do not depict a volcano at all.

- In the short-term, they can trigger cooling. Among other effects, they:

- Produce clouds of ash that can reach into the stratosphere and circulate around the globe within weeks of the eruption. These clouds block out the sun, lowering temperatures.

- Emit sulfur dioxide, hydrogen chloride and hydrogen fluoride gases that can combine with water vapor in the atmosphere and create acid rain.

- Eject sulfur dioxide, which is converted into sulfuric acid. Sulfuric acid condenses rapidly into sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere, which reflect light from the sun back into space, resulting in a cooling effect.

- Over a long period of time, extensive volcanic eruptions can warm the climate.

- Volcanoes release large quantities of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that trap heat from the sun and contribute to global warming. Nowadays, the amount of carbon dioxide released by volcanoes is insignificant compared to that released by humans, but in the past, massive and long-lasting volcanic eruptions have warmed Earth’s climate significantly.

- In the short-term, they can trigger cooling. Among other effects, they:

- The climate changes caused by volcanoes can have devastating social and economic effects. Temperature decreases, torrential rains and acid rains often cause crop failures that lead to famines, and both famines and climate changes can cause diseases. Many works of art across time, cultures and media seek to capture these themes, in addition to volcanoes and volcanic eruptions themselves.

Examples of Volcanoes in Art

Pierre-Jacques Volaire, French, 1729–c. 1790-1800. The Eruption of Vesuvius, 1771. Oil paint on canvas. Purchased by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1978.

THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO.

- This painting depicts the 1771 eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Naples, Italy. It is just one example of the obsession artists in the Age of Enlightenment had with natural disasters.

- The Age of Enlightenment was an intellectual movement in the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe surrounding ideas about God, reason, nature and humanity that inspired shifts in art, philosophy and politics.

- Vesuvius is most famous for its 79 CE eruption that destroyed the ancient Roman city of Pompeii, near Naples, Italy, but it was very active throughout the 18th century, erupting almost every decade.

- Volaire was born in France but spent most of his adult life in Naples. He painted scenes of the Italian countryside for English and German tourists, until the 1771 eruption of Vesuvius when he switched to almost exclusively painting the volcano.

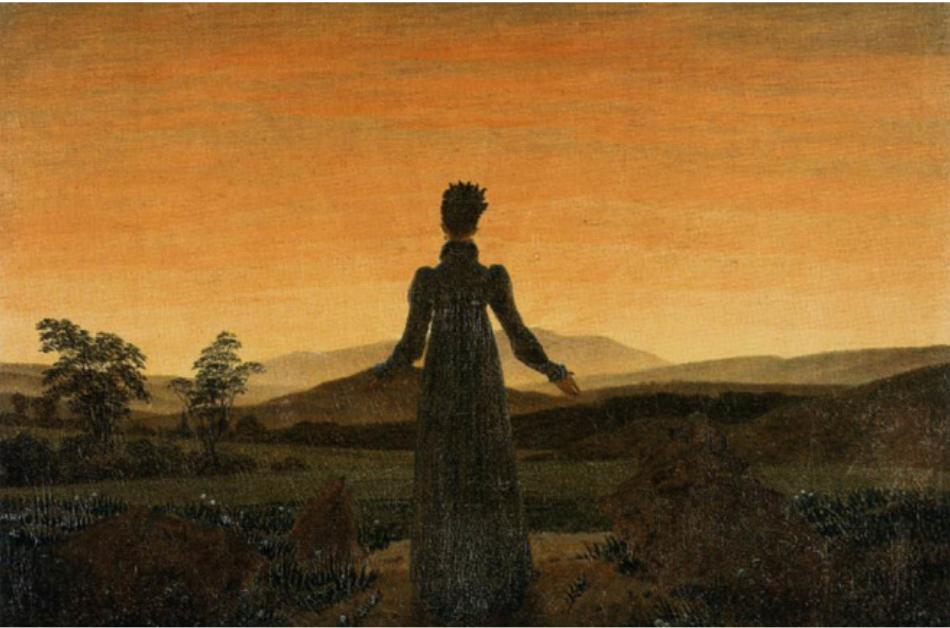

Caspar David Friedrich, German, 1774–1840. Woman in Front of Setting Sun, c. 1818. Oil paint on canvas. Acquisition was funded by the German Center for The Loss of Cultural Property.

MUSEUM FOLKWANG.

- One of the striking features of this painting is the golden-orange hues of the sky. They were inspired by what the sky actually looked like in Europe after the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in 1815, about 7,000 miles (11,000 kilometers) away. The eruption, the largest one in recorded history, sent sulfur dioxide and volcanic ash into the air, engulfing the globe and blocking out the sun. This caused a volcanic winter in which average global temperatures dropped by 3°C.

- Cold temperatures, torrential rains and acidic ash that settled on agricultural fields caused massive crop failures, which then resulted in world-wide famine lasting until 1818. Locally, people died from the initial volcanic blast. Globally, they suffered from starvation as a result of famine and diseases, including severe respiratory infections from inhaling volcanic ash, diarrheal disease from drinking water contaminated with ash, and famine-related diseases such as cholera and typhus.

- Friedrich, who is considered to be the most important painter of the German Romantic movement and is known for his allegorical landscapes, tried to convey a sense of hope beyond the social and environmental disaster by painting the woman looking past the dead crops onto greener pastures.

James Mallord William Turner, English, 1775–1851. Decline of the Carthaginian Empire, 1817. Oil paint on canvas. Part of the Turner Bequest of 1856.

TATE BRITAIN.

- This painting also features a volcanic sky. It depicts the death and destruction in the final days of the Carthaginian Empire, which stretched across southern Spain and northern Africa and was the most powerful empire in the world before the Roman Empire. Although Carthage fell in 146 BCE, long before the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, Turner painted the sky as he experienced it in England in the wake of this eruption: hazy and filled with ash.

- Turner was an English Romantic landscape painter known for his studies of light, color and the atmosphere.

James Mallord William Turner, English, 1775–1851. Chichester Canal, 1828. Oil paint on canvas. Part of the Turner Bequest of 1856.

TATE BRITAIN.

- An ethereal sunset, caused by the volcanic aerosols shot into the air by the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, hangs over the Chichester Canal in southern England in this piece by Turner.

James Mallord William Turner, English, 1775-1851. Study of Sky, c. 1816-1818. Watercolor on paper. Part of the Turner Bequest of 1856.

TATE BRITAIN.

- Turner’s “Skies” sketchbook contains 65 paintings done between 1816 and 1818 in which he studied clouds, sunsets and moonlight. Many of them show a hazy sky that was the result of volcanic ash in the air over Europe after the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia.

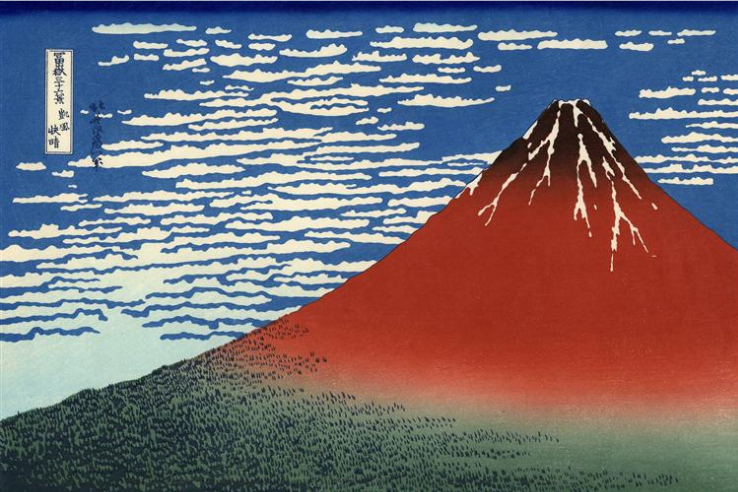

Katsushika Hokusai, Japanese, 1760–1849. Fuji, Mountains in Clear Weather (Red Fuji), 1831. Color woodblock print on paper.

PRIVATE COLLECTION.

Katsushika Hokusai, Japanese, 1760–1849. The Great Wave off Kanagawa, 1831. Color woodblock print on paper.

PRIVATE COLLECTION.

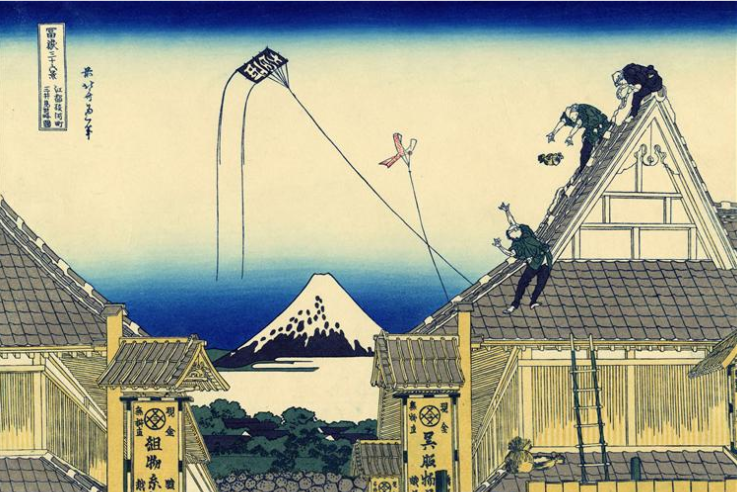

Katsushika Hokusai, Japanese, 1760–1849. Mitsui Shop on Suruga Street in Edo, c. 1831. Color woodblock print on paper.

TOKYO FUJI ART MUSEUM.

Katsushika Hokusai, Japanese, 1760–1849. The Fields of Sekiya by the Sumida River, 1823-1831. Color woodblock print on paper.

BRITISH LIBRARY.

- Printmaker and painter Katsushika Hokusai produced a series of paintings using the woodblock style of ukiyo-e that pays homage to Mount Fuji in Japan. The large composite cone of the volcano is depicted in all of these selected paintings from the series.

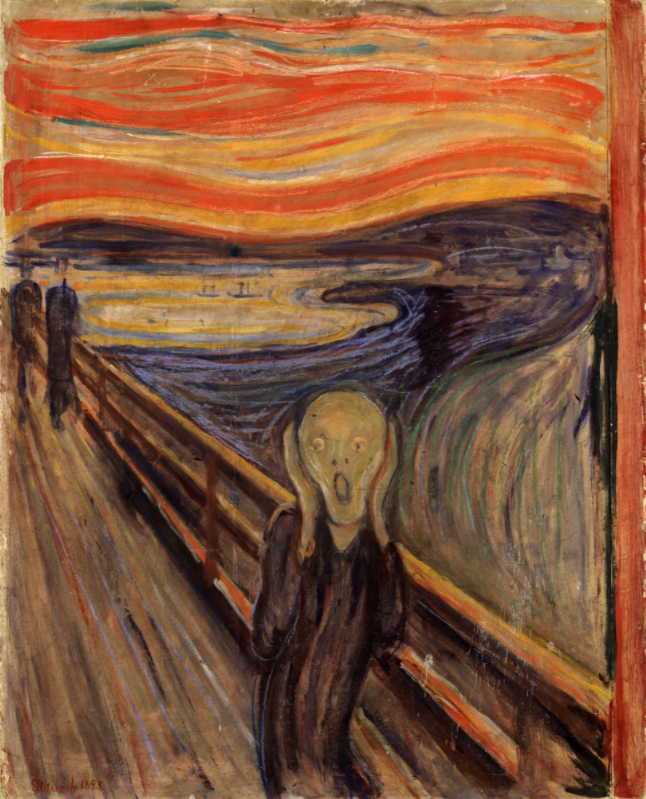

Edvard Munch, Norwegian, 1863–1944. The Scream, 1893. Tempera and grease pin on cardboard. Gift of Olaf Schou in 1910.

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NORWAY.

- Like Woman in Front of Setting Sun (above), The Scream also features a sky of red and orange hues. However, the inspiration for this painting was the eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia in 1883. Krakatoa’s effects on global climate were not nearly as extreme as those of Mount Tambora, but in the year following its eruption, summer temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere fell by as much as 2℃. Some areas also had other strange weather events, such as the record amounts of rainfall in California.

- Munch, a painter, illustrator and writer known for his experimental artistic techniques, was supposedly on a walk with friends in Norway when the sky turned “blood red.” The sunset was being colored by the volcanic ash and dust that hung in the air from the Krakatoa eruption. The anxiety he felt in that moment is depicted in this famous painting, completed ten years after the eruption.

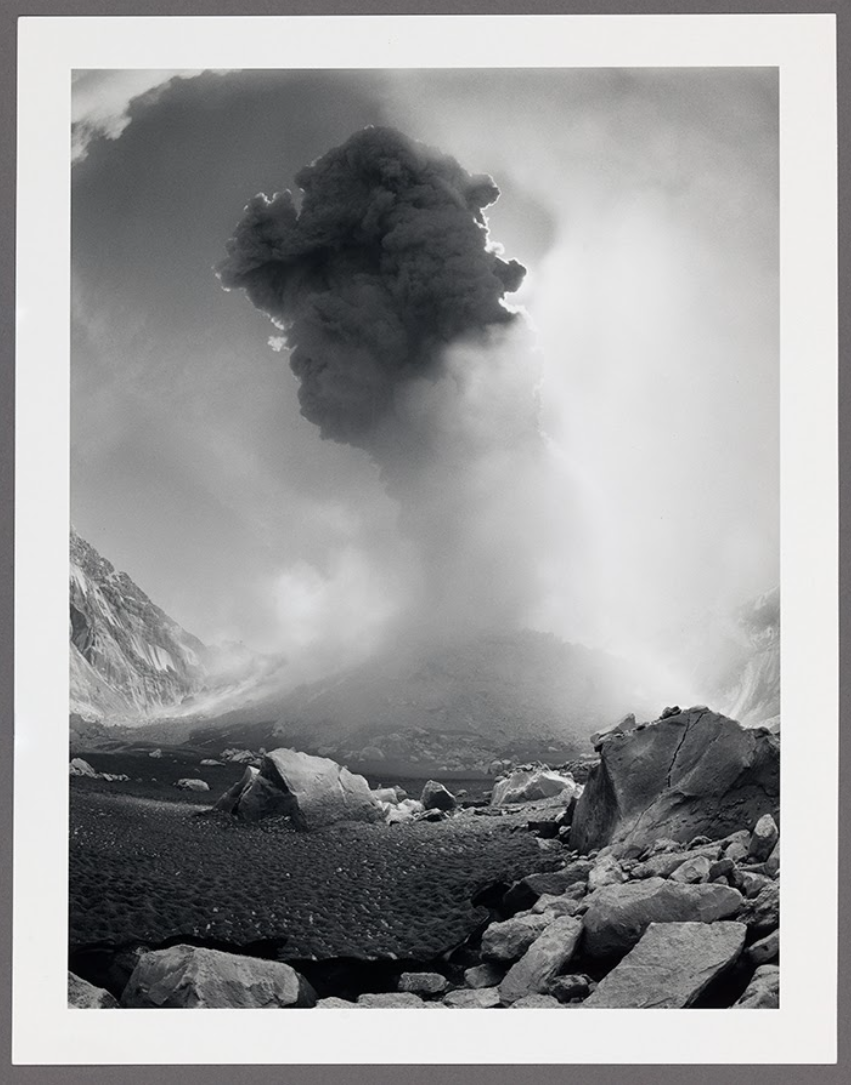

Mathias van Hesemans, American, 1946-. Mount St. Helens Eruption, 1983. Photograph, gelatin silver print. Gift of Robert Flynn Johnson in memory of Minna Flynn Johnson, class of 1936.

SMITH COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART. SC 2020.13.2

- This is a photograph of the 1980 Mount St. Helens Eruption in Washington, USA, the deadliest volcanic eruption in US history. This eruption caused close to 60 deaths and over $1 billion in property damages (an equivalent of about $3.5 billion today). Volcanic ash from this eruption settled across 11 US states and five Canadian provinces.

- This eruption had virtually no global climate effects because it ejected very little sulfur dioxide, which, when emitted in large quantities, results in cooling by blocking sunlight from entering the atmosphere. However, the ash cloud had striking effects on local weather. On the day of the eruption, portions of eastern Washington experienced a drop in temperature by as much as 8℃ as the cloud blocked out incoming sunlight. The ash cloud also kept the region 8-12℃ warmer than normal overnight, because it trapped infrared radiation that is usually lost to the atmosphere when the sun is not actively warming the planet. The weather effects only lasted for a few days and disappeared as the ash cloud thinned and moved east.

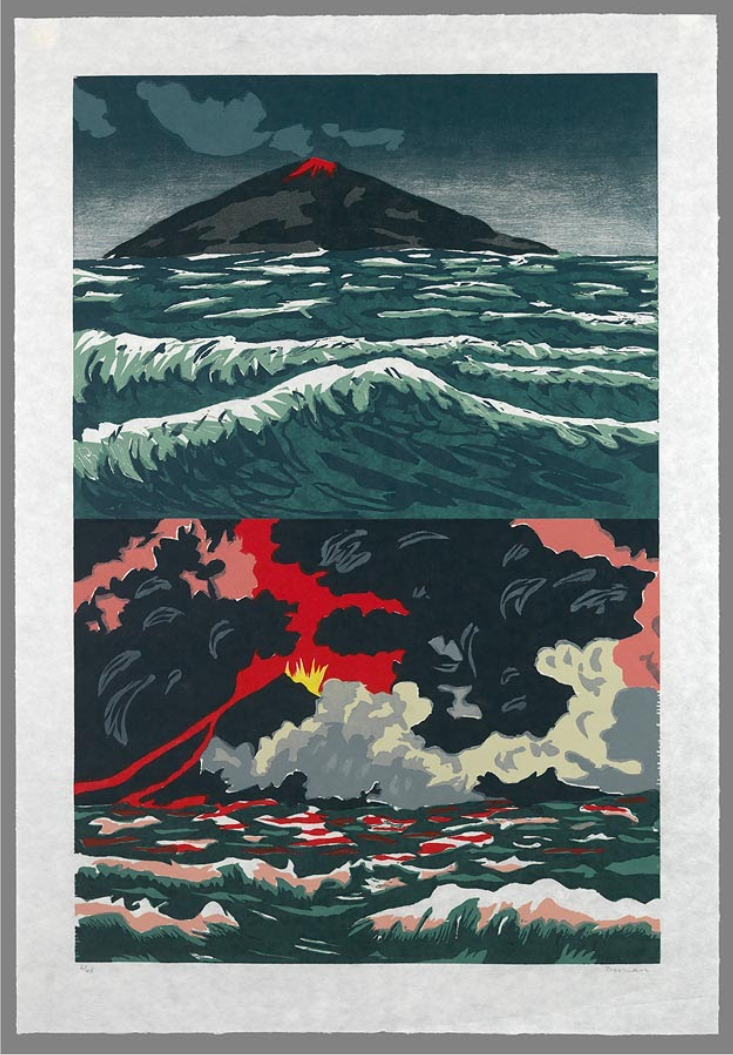

Richard Bosman, Australian, 1944-. Volcano, 1989. Woodcut printed in color on Kozo white paper sheet. Gift of Wilson and Eliot Nolen (Eliot Chace Nolen class of 1954).

SMITH COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART. SC 2010.65.9

- This piece contrasts the differences in environmental conditions before and during a volcanic eruption.

- Before the eruption (top), the skies are blue and clear and the ocean is relatively calm.

- During the eruption (bottom), the skies are darkened by huge clouds of ash and smoke from the volcano. The turbulence of this event is further highlighted by the rough seas and the reflection of lava in the water.

From Willis, 2016.

- The Tigua People of Ecuador in South America create bright and vibrant art about life amongst the Andean volcanoes. On mainland Ecuador, there are more than 30 volcanoes, both active and extinct. The Tiguan paintings are traditionally done on sheepskin, but they also weave images into fabric, as seen above.

Further Exploration

- The colors of the sky in sunset paintings can be used to estimate the amount of ash particles in the air at the time the painting was created. Researchers analyzed the ratio of red to green in paintings done between 1500 and 2000 CE, a period in which there were more than 50 volcanic eruptions worldwide, to determine an approximate amount of volcanic ash in the air. They then compared the colors to the actual amount of ash determined from ice core samples and other measurements and found the paintings to be remarkably accurate.

References and Additional Resources

- “1980 Eruption of Mount St. Helens.” Wikipedia. 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1980_eruption_of_Mount_St._Helens.

- “Caspar David Friedrich.” Caspar David Friedrich: The Complete Works. n.d. https://www.caspardavidfriedrich.org/.

- Chamot, M. “J.M.W. Turner.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 1999. https://www.britannica.com/biography/J-M-W-Turner.

- “Chichester Canal.” Tate Britain. n.d. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-chichester-canal-n00560.

- Duignan, B. “Enlightenment.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 1998. https://www.britannica.com/event/Enlightenment-European-history.

- “Frau vor der untergehenden Sonne.” Museum Folkwang. n.d. http://collection-online.museum-folkwang.de/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=direct/1/ResultListView/result.t2.collection_list.$TspTitleImageLink$0.link&sp=10&sp=Scollection&sp=SfieldValue&sp=0&sp=0&sp=3&sp=SsimpleList&sp=0&sp=Sdetail&sp=0&sp=F&sp=T&sp=21.

- “Fuji, Mountains in Clear Weather (Red Fuji).” WikiArt: Visual Art Encyclopedia. 2020. https://www.wikiart.org/en/katsushika-hokusai/fuji-mountains-in-clear-weather-1831.

- Harpp, K. “How Do Volcanoes Affect World Climate?” Scientific American. 2005. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-do-volcanoes-affect-w/.

- Learn, J. R. “How Mount Tambora and Other Volcanic Eruptions Inspired Artistic Masterpieces.” Discover. 2021. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/how-mount-tambora-and-other-volcanic-eruptions-inspired-artistic.

- Mass, C. “Weather Impacts of the Mount Saint Helens Eruption.” Cliff Mass Weather Blog. 2013. https://cliffmass.blogspot.com/2013/05/weather-impacts-of-mount-saint-helens.html.

- Mayer, J. and Young, L. J. “Art and History Shaped by Volcanic Winters.” Science Friday. 2019. https://www.sciencefriday.com/articles/the-art-and-history-shaped-by-volcanic-winters/.

- “Skies Sketchbook.” Tate Britain. n.d. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/sketchbook/skies-sketchbook-65800/109.

- Singer, J. W. “Painting of the Week: Pierre-Jacques Volaire, Eruption of Mount Vesuvius.” Daily Art Magazine. 2020. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/painting-of-the-week-pierre-jacques-volaire-eruption-of-mount-vesuvius/.

- “The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire.” Tate Britain. n.d. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-the-decline-of-the-carthaginian-empire-n00499.

- “The Eruption of Vesuvius.” The Art Institute of Chicago. n.d. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/57996/the-eruption-of-vesuvius.

- “The Fields of Sekiya by the Sumida River.” WikiArt: Visual Art Encyclopedia. 2020. https://www.wikiart.org/en/katsushika-hokusai/the-fields-of-sekiya-by-the-sumida-river-1831.

- “The Great Wave of Kanagawa.” WikiArt: Visual Art Encyclopedia. 2020. https://www.wikiart.org/en/katsushika-hokusai/the-great-wave-of-kanagawa-1831.

- “The Scream.” National Museum of Norway. n.d. https://www.nasjonalmuseet.no/en/collection/object/NG.M.00939.

- “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.” Wikipedia. 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirty-six_Views_of_Mount_Fuji#Exhibitions.

- “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji: Mitsui Store at Suruga-cho in Edo.” Tokyo Fuji Art Museum. n.d. https://www.fujibi.or.jp/en/our-collection/profile-of-works.html?work_id=1166.

- “Volcanoes Can Affect Climate.” United States Geological Survey. n.d. https://www.usgs.gov/natural-hazards/volcano-hazards/volcanoes-can-affect-climate.

- Williams, J. “The Epic Volcanic Eruption That Led to the ‘Year Without a Summer.’” The Washington Post. 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2015/04/24/the-epic-volcano-eruption-that-led-to-the-year-without-a-summer/.

- Willis, I. “Artists Draw Inspiration from Fire and Ash.” Earth Magazine. 2016. https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/artists-draw-inspiration-fire-and-ash.

- Wood, G. D. Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the World. Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Zerefos, C. S., et al. “Further Evidence of Important Environmental Information Content in Red-to-Green Ratios As Depicted in Paintings by Great Masters.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, vol. 14, no. 6, 2014, pp. 2987-3015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-2987-2014.

- Zielinski, S. “200 Years After Tambora, Some Unusual Effects Linger.” Smithsonian. 2015. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/200-years-after-tambora-volcano-eruption-unusual-effects-linger-180954918/?page=7.