What happened?

- During the 1400s, between 54 and 61 million Indigenous peoples lived in North, Central, and South America. They engaged in agriculture, lived in complex and varied societies, managed their land, and supported their communities (image below).

- In 1492, Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas, beginning an era of European colonialism that completely disrupted Indigenous ways of life. European colonists waged wars and committed atrocities against Indigenous people and brought foreign flora and fauna that disrupted native ecosystems. Europeans spread diseases such as measles, smallpox, influenza, and the bubonic plague that ravaged Indigenous populations and their livestock, who had no natural immunity to them. Recent research theorizes that leptospirosis alone, a disease carried by rats transported on ships from Europe, was responsible for killing an estimated 75% to 95% of the population. Colonization resulted in the devastating loss of Indigenous life. Over the next two centuries, the Indigenous population was reduced to a mere 6 million people in the genocide event termed the ‘Great Dying’ by Western scholars.

Colored watercolor drawing of a Powhatan village of Secoton, completed in 1587 by artists Theodor de Bry and John White (from Encyclopedia Britannica).

How is this related to climate?

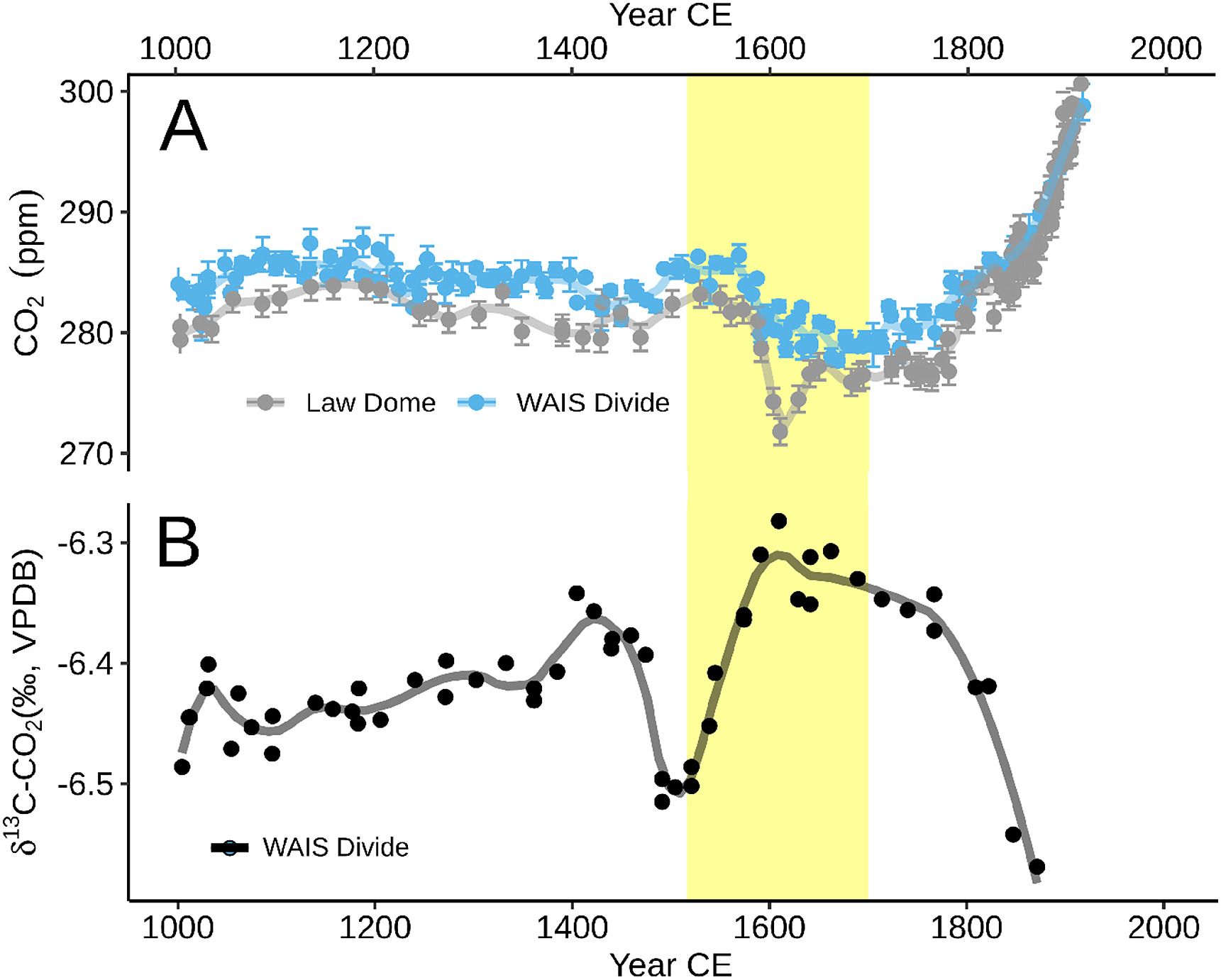

- The loss of Indigenous lives greatly affected the environment and the land the people lived on. With only about 10% of the Indigenous population of the Americas remaining, as much as about 55 million hectares (212,000 square miles) of land (an area about the size of France) that had been cleared and maintained for centuries went uncared for. Wild vegetation repopulated the land, leading to an increase in biomass that pulled carbon from the atmosphere. Atmospheric carbon levels dropped by seven to ten parts per million, as evidenced by high-resolution ice cores (image below), causing a drop of about 0.15℃ in global temperatures.

Global trends in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). Graph A shows the CO2 concentrations over time recorded in two Antarctic ice cores: Law Dome (gray) and West Antarctic Ice Sheet Divide (blue). Graph B shows terrestrial uptake of carbon. The yellow box is the time span of the ‘Great Dying’ event. Notice that CO2 concentrations decreased and terrestrial uptake of carbon increased during the ‘Great Dying,’ indicating that plants were taking greater amounts of carbon out of the atmosphere (from Koch and others, 2019).

- This drop in global temperatures may have slightly intensified the Little Ice Age, a period of widespread cooling and a drop in average temperatures in Europe and North America from around 1300 to 1850 CE.

Why is this important?

- As an early example of anthropogenic, or human-caused, climate change, the ‘Great Dying’ highlights several key points about how we think about current anthropogenic climate change and its mitigation:

- The ‘Great Dying’ shows that colonialism, along with industrialism, is one of the causes of climate change.

- The ‘Great Dying’ highlights the importance of centering Indigenous voices and knowledge in conversations about caring for the environment and addressing climate change.

- The Industrial Revolution is typically considered to be the start of anthropogenic climate change, but the ‘Great Dying’ supports the idea that agricultural practices, starting about 7000 years ago, may have been the first instance of humans affecting the climate. This idea was proposed by William Ruddiman in 2003 as “the early anthropogenic hypothesis.”

References and additional resources

-

- Architect of the Capitol. “Landing of Columbus. ”https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/landing-columbus.

- Blaustein, R. “William Ruddiman and the Ruddiman Hypothesis.” Minding Nature, vol. 8, no. 1, 2015. https://www.humansandnature.org/william-ruddiman-and-the-ruddiman-hypothesis.

- Cronon, W. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. Hill & Wang, 2003.

- Davis, H. and Todd, Z. “On the Importance of a Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, vol. 16, no. 4, 2017, pp. 761–80.

- Degroot, D. “Did Colonialism Cause Global Cooling? Revisiting an Old Controversy.” Historical Climatology. 2019. https://www.historicalclimatology.com/features/did-colonialism-cause-global-cooling-revisiting-an-old-controversy.

- Denevan, W. M., editor. The Native Population of the Americas in 1492. The University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

- Downes, N. “‘Great Dying’ in Americas disturbed Earth’s climate.” University College London. 2019. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2019/feb/great-dying-americas-disturbed-earths-climate.

- Koch, A., Brierly, C., Maslin, M. M., and Lewis, S. L. “Earth System Impacts of the European Arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492.” Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 207, 2019, pp. 13–36. DOI: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277379118307261

- Ruddiman, W. F., He, F., Vavrus, S. J., and Kutzbach, J. E. “The Early Anthropogenic Hypothesis: A Review.” Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 240, July 2020, p. 106386. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277379120303486.

- “Surviving New England’s Great Dying.” NH PBS. 2021. https://nhpbs.org/greatdying/.

- Varva, K. “‘Great Dying’ of Indigenous Peoples during Colonization of America Caused Earth’s Climate to Change.” New York Daily News, 2019. https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/ny-news-great-dying-colonization-climate-change-20190131-story.html.