What happened?

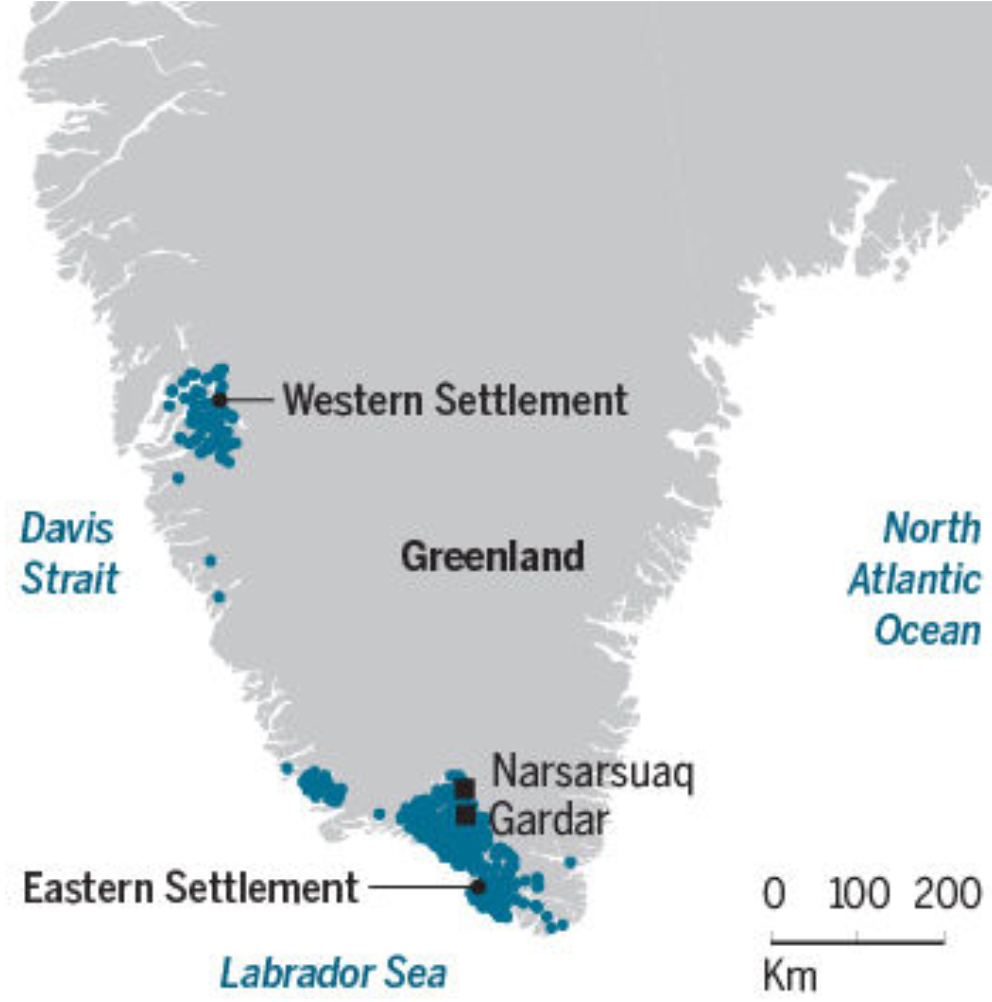

- A group of seafaring Norse settlers from mainly Denmark, Sweden, and Norway in Scandinavia, established settlements in Greenland in the late 10th century (map below). These settlements were occupied for about 500 years before disappearing somewhat mysteriously in the middle of the 15th century.

The two Norse settlements in southern Greenland, known as the Western and Eastern Settlements (Kintisch, 2016).

- Archaeologists propose two main hypotheses for the Norse settler’s disappearance in Greenland:

- The entire population perished in Greenland.

- The Norse migrated back to mainland Europe.

- This hypothesis appears to be slightly more likely because very few valuables, such as jewelry, cups, candelabras, and other metal objects, were left in Greenland. If the pioneers had sailed back to Europe, they likely would have taken these items with them.

- Whichever hypothesis is correct, a drop in the population would have been catastrophic to the small settlements, which barely reached a combined number of 2,500 people at their peak.

- People of Norse descent in modern-day North America most likely trace their ancestry back to a second wave of immigration in the mid-19th century. Waves of Norwegian and Scandinavian migrants settled in the Midwestern United States from the 1850s to the 1920s, mostly due to the appeal of abundant American farmland and economic opportunities.

How is this related to climate?

- Norse settlements in Greenland were facing several stresses shortly before they were abandoned in the middle of the 15th century, and a changing climate was one of them.

- The settlers lived in harsh cold and dry environments that were just barely survivable, so small changes in temperature, precipitation, or sea level could have big impacts.

- The Black Death spread across Europe during the 14th century. While the plague did not actually reach Greenland, it killed about half of Norway’s population, and because Greenland relied heavily on Norway for imported goods, this affected Greenland too.

- The value of ivory plummeted. The Norse likely originally settled in Greenland to hunt walruses for ivory tusks, which they sold back in Norway. In the 14th century, ivory from Russian walruses and African elephants, which was cheaper and easier to obtain, flooded the market, causing the prices of Greenland ivory (image below) to fall, destabilizing a large part of the settler economy.

12th century Lewis chessmen carved from Greenland ivory (from Kintisch, 2016).

-

- The climate became exceptionally erratic and unstable, reaching both record high and record low temperatures, before becoming consistently cold. A recent study also found that drought conditions resulted in summers becoming increasingly dry.

- The Norse in Greenland tried to adapt to the changing climate, but ultimately it was not enough.

- Farming was a central part of the Norse identity, and the pioneers grew grain and raised livestock, in addition to hunting walruses and seals. As the climate worsened, crop and meat production faltered. Colder temperatures meant that cows had to be kept inside for more months of the year. As a result, they could not graze and more hay had to be produced to feed them, which was increasingly difficult as the growing seasons got shorter and drier.

- The settlers had to rely more heavily on what they caught from the ocean for food and less on their farms. This is evidenced by the ratios of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in bones found in Norse graveyards. Terrestrial animals have different ratios of these isotopes than marine animals, and these ratios are passed on to the people that eat them. The bones show that over time, the Norse ate more marine protein and less terrestrial protein.

- Hunting at sea eventually became challenging as well, as ships were lost and men perished in stormier and icier seas.

- The stresses mounted as the weather worsened and eventually the Norse could no longer hold on.

- The changes in climate were part of the onset of the Little Ice Age, a period of widespread cooling and a drop in average global temperatures from around 1300 to 1850. Natural fluctuations in atmospheric pressure, known as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), may have also been responsible for bringing cold and dry air to Greenland at this time.

- Climate alone did not cause the downfall of Greenland’s pioneers. After all, they remained there for about two centuries after the climate started to cool. However, a cooling climate was an additional obstacle that they had to face – one that may have just pushed them over the edge.

- Climate changes today are making it more difficult to study the factors that contributed to the end of Norse settlements in Greenland. Permafrost preserves bone, hair, feathers, cloth, and other archaeological evidence, and the permafrost is melting due to rising global temperatures. As the permafrost melts, this evidence is lost.

- The pioneers’ story is a warning to modern societies facing climate changes. The Norse were flexible, highly adaptable, and resilient to changes in their environment, and yet they still had to abandon their settlements.

Further Exploration

- Pre-Norse northern European societies also had to deal with a changing climate and did so by regularly adapting their crop cultivation and livestock farming practices. From around 300 to 800 CE, northern Europe experienced frequent cold spells driven by volcanic eruptions, which released gas and ash into the atmosphere, blocking out the sun. This period was known as the Dark Ages Cold Period (DACP).

- Evidence for the cold spells comes from calcium carbonate deposits in lake sediment cores. Biotic activity, such as photosynthesis and the formation of shells in mollusks and other organisms, results in the precipitation of calcium carbonate. During warmer periods, biotic activity is increased, so more calcium carbonate is deposited. The opposite is true for colder periods.

- Communities either relied more on crops or more on livestock for food depending on climate conditions at a given time. During warmer phases, wheat, barley, and rye were staple parts of the diet, as evidenced by high levels of pollen grains in lake sediment cores. During colder phases, crop yields suffered, so people shifted to meat production. This is evidenced by high levels of Sordaria, a fungus that lives in animal feces, in lake sediment cores. During the Viking Age, a period from the 8th to 11th century when Norsemen engaged in conquering and settling land across Europe and North America, the climate was warmer and more stable, so crop cultivation and livestock farming could take place at the same time.

References and additional resources

- Campbell, G. “Norse America: The Story of a Founding Myth.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Cooper, L. “What Really Happened to Greenland’s Vikings?” Visit Greenland. n.d. https://visitgreenland.com/articles/what-really-happened-to-greenlands-vikings/.

- Dacey, J. “Food Security Lessons from the Vikings.” Eos. 2021. https://eos.org/articles/food-security-lessons-from-the-vikings.

- Zhao, B., Castañeda, I. S., Salacup, J., Thomas, E. K., Daniels, W. C., Schneider, T., de Wet, G. A., and Bradley, R. “Prolonged drying trend coincident with the demise of Norse settlement in southern Greenland.” Science Advances. 2022. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abm4346

- Strickland, A. “The surprising reason why Vikings abandoned a successful settlement.” CNN. 2022. https://www.cnn.com/2022/03/24/world/why-vikings-left-greenland-scn/index.html

- Folger, T. “Why Did Greenland’s Vikings Vanish?” Smithsonian. 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-greenland-vikings-vanished-180962119/

- Kintisch, E. “Why Did Greenland’s Vikings Disappear?” Science. 2016. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/11/why-did-greenland-s-vikings-disappear.

- Lane, R. K. “Lake.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 2019. https://www.britannica.com/science/lake.

- Northwestern University. “Study Shows that Vikings Enjoyed a Warmer Greenland.” Phys. 2019. https://phys.org/news/2019-02-vikings-warmer-greenland.html.

- The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Viking.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Viking-people.