What happened?

- Following Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, the Roman Republic ended with Octavian becoming the first Roman emperor in 27 BCE. This marked the beginning of the Roman Empire.

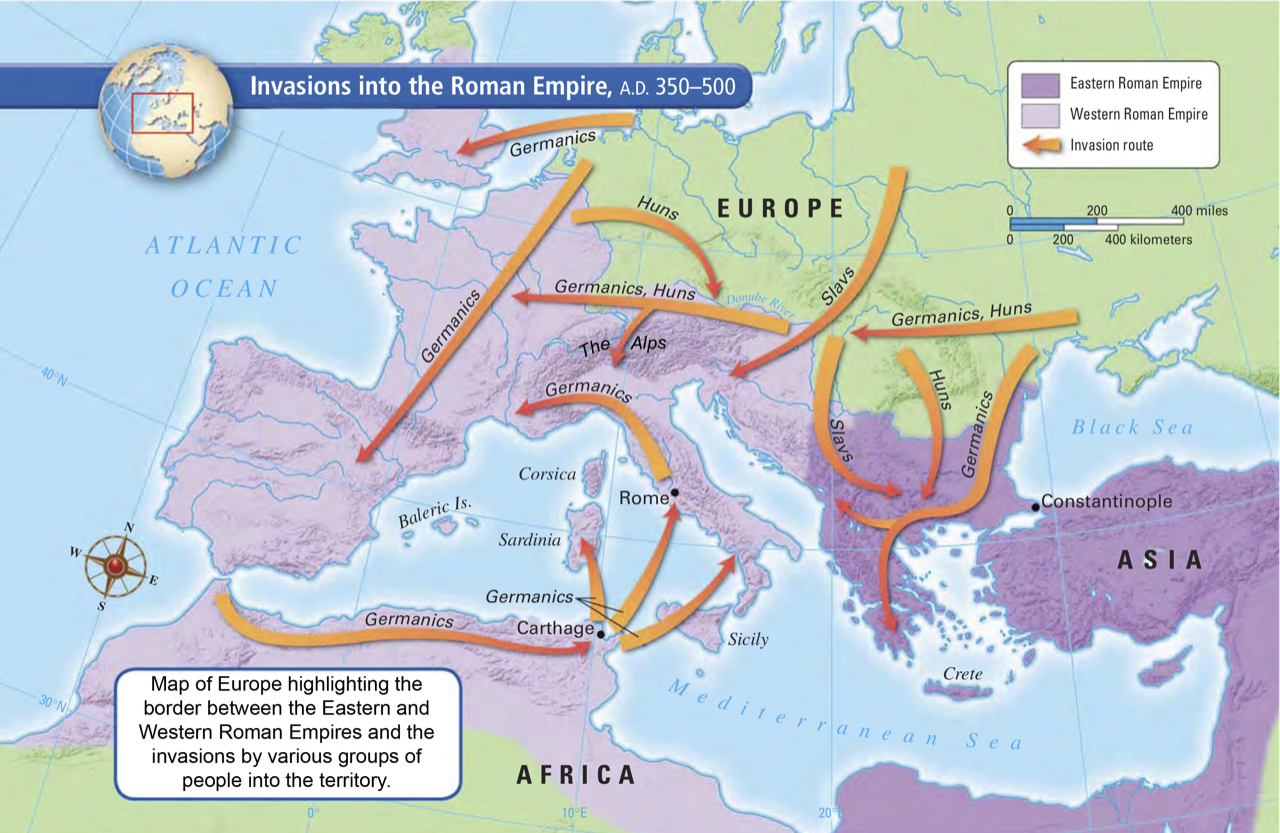

- Starting in the 300s CE, the previously powerful and influential Western Roman Empire, shown in the map below, experienced increasing turmoil that lead to its unravelling and collapse in the 500s.

- Political turmoil, cultural change, disease, and socioeconomic instability contributed to the unrest, as well as the invasion of Persian and Germanic peoples during the Migration Period (c. 375-568 CE, a time of widespread migration of and invasions by peoples within or into the Roman Empire).

How is this related to climate?

- At the beginning of the Common Era (CE), the weather in southern Europe was warm, wet, and stable, which was conducive to the growth of the Roman Empire, as an expanding agrarian society.

- Then, between 200-600 CE, this period of climate stability ended, leading to a period of climate variability that caused crisis and instability within the Roman Empire. Disease spread and dry weather caused agrarian issues.

- Mountain passes in the Alps melted during the end of the warm period at the beginning of the CE, and the later climate variability created even less ideal temperatures and conditions in Northern Europe.

- Germanic peoples migrated to the relative warmth of Mediterranean Europe through the newly melted Alpine passes (map below), threatening the Western Roman Empire. Their migration was in part driven by their need for more resources as theirs became scarce due to the changes in environmental conditions.

- Germanic peoples migrated to the relative warmth of Mediterranean Europe through the newly melted Alpine passes (map below), threatening the Western Roman Empire. Their migration was in part driven by their need for more resources as theirs became scarce due to the changes in environmental conditions.

- Furthermore, Roman manipulation of the land around them (moving rivers, slashing and burning forests, draining basins, etc.) exposed unfamiliar parasites and triggered ecological change.

- The climate instability added to and exacerbated the widespread political, cultural, and socioeconomic issues, making it part of the numerous factors that contributed to the Western Roman Empire’s decline.

Modified from World History: Ancient Civilizations, 2006, pp. 503.

Further Investigation

- The issues within the Roman Republic, which came to a head with Caesar’s assassination may have been exacerbated by the megaeruption of the Alaskan volcano Okmok. This generated extreme climate conditions across the Northern Hemisphere and could have contributed to widespread famine.

- Spikes in light-blocking sulfate particles and volcanic shards in ice cores at 43 BCE represent evidence of this eruption. These volcanic aerosols could have cooled southern Europe and northern Africa by up to 7°C. Roman and Greek philosophers wrote about cold weather and famine around this time period, and Egypt experienced similar famines.

- Problems within the Republic that lead to its end were primarily political in nature and on the level of the elite, and were not related to popular revolution or a subsistence crisis, even though regional responses to a changed climate may have also played a role.

- The climate instability peaked in the 6th century, likely as a result of the spasm of volcanic activity in the 530s and 540s CE that led to widespread cooling in Europe and across the globe, which endured for at least 150 years. Two volcanic eruptions were particularly impactful on the climate during this time period, one in 535 or 536 CE and one in 539 or 540 CE. The eruption in 535 or 536 CE probably impacted the Western Roman Empire the most directly.

- The eruptions shot clouds of volcanic ash into the air. This blocked out sunlight, causing an average drop in global temperatures of 2°C, the greatest in 2,000 years.

- The lack of sunlight and drop in temperatures lead to mass crop failure. Droughts, which can also be triggered by volcanic eruptions, may have contributed as well.

- These eruptions also impacted the Maya civilization in Central America.

- Disease and climate were also connected: all three major plagues (the Antonine Plague, the Cyprian Plague, and the Justinianic Plague) that contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire happened during times of climate instability and were also facilitated by Roman connectivity and extensive trade networks, which spread the diseases further.

- Plagues commonly spill over to humans from wild rodents. Such plague outbreaks often follow periods of warm and/or wet conditions that are favorable for vegetation growth and for increases in rodent population density.

- Plagues commonly spill over to humans from wild rodents. Such plague outbreaks often follow periods of warm and/or wet conditions that are favorable for vegetation growth and for increases in rodent population density.

References and additional resources

- Büntgen, U., et al. “2500 Years of European Climate Variability and Human Susceptibility.” Science, vol. 331, no. 6017, 2011, pp. 587–582. DOI: 10.1126/science.1197175.

- Carnine, D. World History: Ancient Civilizations (1st ed). McDougall Littell, 2006.

- Harper, K. “How Climate Change and Plague Helped Bring Down the Roman Empire.” Smithsonian. 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-climate-change-and-disease-helped-fall-rome-180967591/.

- Harper, K. The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire. Princeton University Press, 2017.

- Light, J. A. “Was the Roman Empire a Victim of Climate Change?” PBS. 2011. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/need-to-know/environment/was-the-roman-empire-a-victim-of-climate-change/6724/.

- McConnell, J. R., et al. “Extreme Climate after Massive Eruption of Alaska’s Okmok Volcano in 43 BCE and Effects on the Late Roman Republic and Ptolemaic Kingdom.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 117, no. 27, 2020, pp. 15443–49. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2002722117.

- McCormick, M., et al. “Climate Change during and after the Roman Empire: Reconstructing the Past from Scientific and Historical Evidence.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, vol. 43, no. 2, 2012, pp. 169–220. DOI: 10.1162/JINH_a_00379.

- Prothero, D. R. and Dott, R. H. Evolution of the Earth (8th ed). New York, McGraw-Hill Education, 2010.

- Semenza, J. C., and Menne, B. “Climate Change and Infectious Diseases in Europe.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 9, no. 6, 2009, pp. 365–75. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70104-5.

- Voosen, P. “Alaskan Megaeruption May Have Helped End the Roman Republic.” Science AAAS. 2020. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/06/alaskan-mega-eruption-may-have-helped-end-roman-republic.

- Wazer, C. “The Plagues That Might Have Brought Down the Roman Empire.” The Atlantic. 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/03/plagues-roman-empire/473862/.

- Zielinski, S. “Sixth-Century Misery Tied to Not One, But Two, Volcanic Eruptions.” Smithsonian. 2015. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/sixth-century-misery-tied-not-one-two-volcanic-eruptions-180955858/.