Where is Japanese spoken?

- There are 126 million native Japanese speakers, the vast majority of whom reside in Japan (map below). Japan is the only country with Japanese as its official language. Outside of Japan, a significant number of native Japanese speakers live in the United States and Brazil.

Map of Japan, in the western Pacific Ocean, east of the Asian continent (from Watanabe, 2023).

Climate education in Japan

Climate Education Policies and Programs

- Japan’s greatest climate change threats are hurricanes, floods, and wildfires. Hotter temperatures and changing precipitation patterns are affecting the Pacific monsoon cycle.

- Recent surveys indicate that a significant portion of Japanese citizens are aware of and care about climate change. In a 2021 survey, 88% of participants were concerned about the effects of global warming.

- The majority of Japanese policy on teaching sustainability is focused on general environmental concerns, without much emphasis on climate change specifically. However, the Third Education Promotion Basic Plan, a major education reform policy signed in 2018, aims to encourage collaboration between primary schools, secondary schools, universities, and businesses to promote sustainable development learning. Notably, the policy provided additional support to schools associated with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). One of UNESCO’s key principles is Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). As of 2023, Japan has 1,115 UNESCO-associated schools, which serve as a climate education model for other primary and secondary schools across the country.

- Additionally, Japan has incorporated conservation education into elementary and high schools through several unique programs:

- The first is the study of the Banzu Tidal Flats. The largest natural tide flat in Tokyo Bay, this important ecosystem is a key feature of Kaneda Elementary School education. Students learn about the tide flats through plays and art before gaining hands-on experience with the animals that live there. The elementary school offers multiple programs centered on the tide flat ecosystem, intended to instill in students a sense of responsibility and care for the natural world.

- Another method of environmental education for elementary school students is the Asaza Project. The Asaza (image below) is a pretty yellow flower that faces extinction due to the pollution of lake environments. Despite government measures to protect lake ecosystems, the flower still remains endangered. Local elementary schools have come together to replant these flowers as part of the Asaza Project. Children learn about concepts of sustainability and waste management through their work.

Photograph of flowering asaza (water fringe) plants in a pond. These plants are found throughout Eurasia, and they grow in shallow lakes and ponds throughout Japan (from Flower Database, 2023). Asazas are endangered due to water pollution in Japan.

- You can learn more about climate education in Japan through the Monitoring and Evaluating Climate Communication and Education (MECCE) Project here.

Disaster Preparedness Education

- Much of Japanese climate education centers on natural disaster preparedness. As a string of islands large and small, Japan’s geography makes it vulnerable to natural disasters. Earthquakes from fault lines in the earth’s crust, tropical storms or cyclones moving through “typhoon alley,” and large waves or tsunamis from the ocean that surrounds the land are all a part of life in the nation (image below). Therefore, how to prepare for and react to natural disasters are important aspects of climate education in Japan.

Photograph of Ishinomaki, a city in Japan’s Miyagi prefecture, after the devastating 2011 tsunami that killed over 18,000 people and caused meltdowns at the Fukushima nuclear plant (from Nogi, 2021). The massive tsunami, triggered by a 9.1 magnitude earthquake in the Pacific Ocean, swept debris inland and brought massive destruction along the east coast of Japan.

- Natural disaster preparedness in Japan takes on many different forms. Here are a few examples of instructions and practices that help to prepare for emergencies:

- Both children and adults are expected to memorize the location of evacuation sites, as well as how to get there from home, school, or work. A 2019 advertisement from the Ad Council of Japan targeted families in particular, encouraging them to go on “Disaster Preparedness Walks” (防災散歩 or bōsai sanpo) to memorize evacuation routes, taking note of possible dangerous spots along the way such as tall buildings or rivers. Even if someone is new to an area, signs in Japanese and English leading to evacuation sites help to inform and direct people in emergencies.

- Another means of preparing for a natural disaster is to pre-pack supplies for easy access. A bōsai baggu (防災バッグ) is a bag filled with food, first aid, and other materials useful in case of emergency. Since it is packed into a bag or backpack, it allows people to quickly evacuate their homes with helpful supplies.

- There are also resources regarding natural disasters for foreigners living in Japan. NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) has articles describing what can happen during a natural disaster, and what to do in case you experience one, in easy-to-read Japanese. These can be accessed on their website NHK News Web Easy and include furigana (readings of the kanji characters) as well as definitions of more difficult vocabulary terms.

- Japan’s disaster preparedness education serves as a model for other countries’ response to climate-related catastrophes. In 2015, Japan hosted a UN Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction, educating other countries on their experience with disaster preparation and recovery. While most of their advice revolved around infrastructure upgrades and central and local government cooperation, Japanese officials shared the importance of disaster education.

- Japan’s earthquake and tsunami preparedness strategies can also be applied to climate-related disasters in other parts of the world. Learning how to recognize potential extreme weather events – such as floods, wildfires, storms, and heat waves – and how to respond better prepares communities and saves lives.

Discussion Questions:

- Does your school or region have an evacuation plan in case of a natural disaster? If so, do you think it is effectively communicated to the community?

- What kinds of natural disasters occur in your area? Is it similar to or different from Japan?

- What are some ways that you and your family can prepare for a natural disaster?

Climate and culture in Japan

- Japan has a monsoonal climate, meaning that its weather conditions are primarily controlled by seasonal winds. During the winter monsoon period (late September to late March), eastward winds transport moisture from the Sea of Japan. This brings precipitation to the eastern edge of the country and leaves the western side with dry weather. In the summer monsoon period (early April to early September), reversed winds bring in hot and humid weather to Japan, mainly affecting the western side.

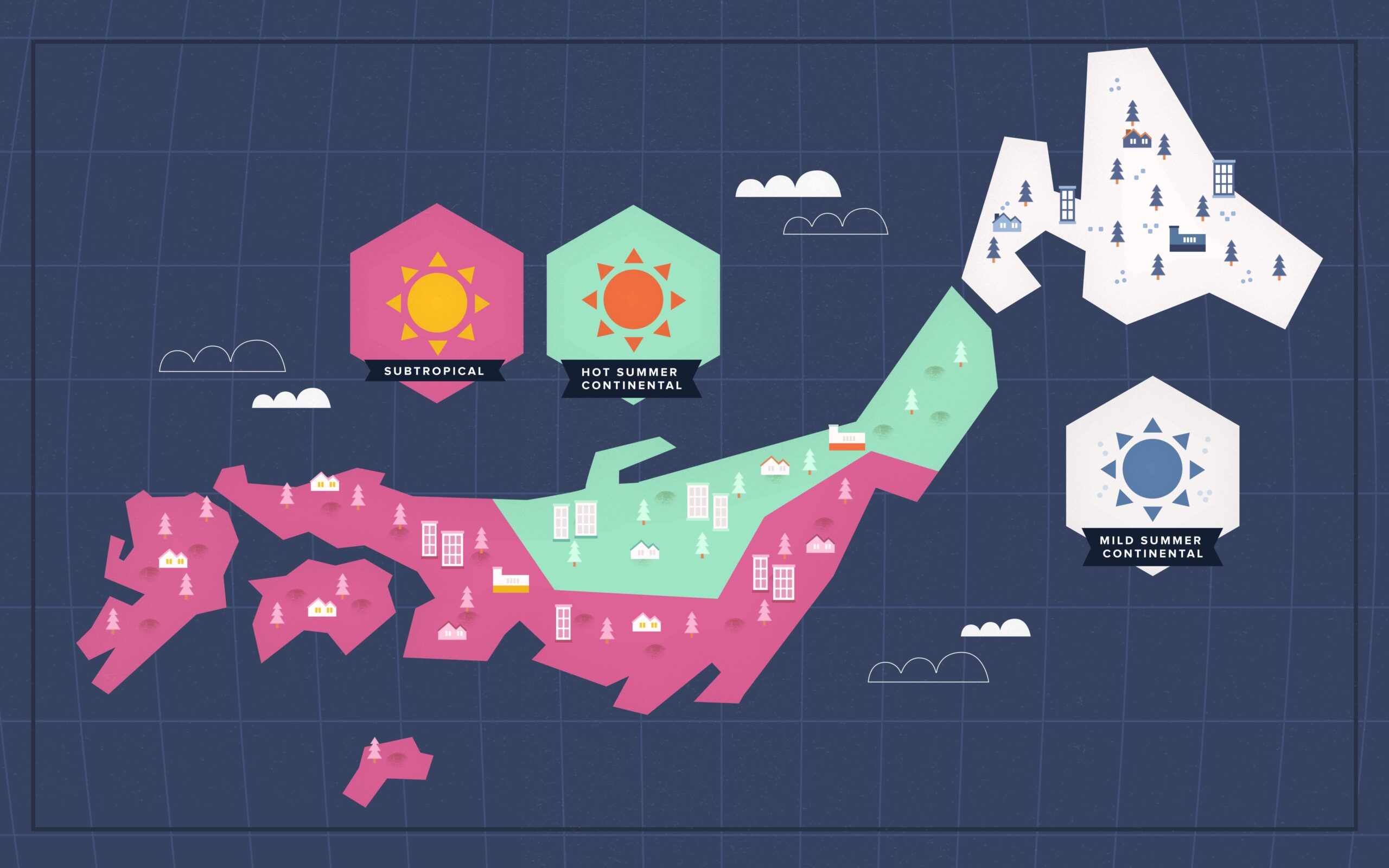

- Temperature and precipitation in Japan vary by latitude and season (artistic map below). In general, temperatures range from -8°C to 8°C in the winter to 21°C to 28°C in the summer. Japan receives roughly 1,020 mm (40 inches) of precipitation annually.

- The effects of anthropogenic (human-induced) climate change are already visible in Japan. Average annual temperatures have increased by 1.0°C in the past century, and sea levels have risen at a rate of 5 mm a year since 1993.

Graphic artwork depicting a map of Japan’s three major climate zones (from Francisco, 2014). The southeastern section in pink has a subtropical climate with a more intense wet season and higher temperatures year-round. The central-western region in green is characterized by a continental climate with especially hot summers. The northern island of Hokkaido in white is more temperate with mild summers and cold winters.

- Climate plays a role in shaping many cultural events in Japan. Japan has an abundance of seasonal festivals and activities that are long-standing traditions.

- In the spring, people gather for Hanami [花見], the custom of viewing the blossoms on cherry and plum trees (image below left). Typically, cherry blossoms reach full bloom in mid-April, but warming temperatures caused by anthropogenic climate change are pushing the start of the season earlier in the year. In 2021, Kyoto blossoms peaked on March 26, the earliest in over 1,200 years.

- In the fall, the changing colors of leaves on the trees, Kōyō [紅葉] similarly encourage people to go out and admire the beautiful scenery (image below right). Kōyō season is between September and December, depending on latitude. To celebrate the beautiful fall foliage, some cities hold Kōyō Matsuri, or Autumn Leaves Festivals, where temples, shrines, and public spaces are decorated with lanterns.

Image of cherry blossoms on the left (from Pixabay, 2019) and autumn maple leaves on the right (from Pixabay, 2015).

- Every February, the Shizuoka Prefecture (just south of Tokyo) holds the Yamayaki Matsuri (Mountain Burning Festival). This ceremony makes way for the renewal and regrowth of spring by burning down dried vegetation in a controlled fire on Mount Omuro. Yamayaki Matsuri can be traced back 700 years and is part of a collective effort to make way for fresh vegetation that sprouts in spring. The event depends on dry-sunny weather since the dead winter grasses that cover the mountain must be dry to ignite.

Photograph of spectators observing Yamayaki Matsuri (Mountain Burning Festival), which occurs annually to clear Mount Omuro for spring vegetation (from Japan Experience, 2018).

-

- Since 1950, Japan has hosted the Sapporo Yuki Matsuri (Sapporo Snow Festival), a celebration in late winter filled with snowball fights, snow and ice sculptures, and local cuisine. Every year, sculptors use over 30,000 tons of snow. In 2019, northern Japan received record-low winter snow, forcing festival organizers to import snow for the Sapporo Snow Festival from nearby towns.

Photograph of festival goers riding a miniature railroad through a Cup of Noodle snow sculpture at the 2020 Sapporo Snow Festival (from Jozuka, 2020).

- The climate also has a significant impact on traditional foods in Japan. For example, rice and fish are two of Japan’s most important staple foods. The average Japanese consumes 50 kg (110 pounds) of rice per year, and fish is a part of many traditional foods. Anthropogenic climate change is threatening rice farming and the Japanese fishing industry. Rising temperatures and atmospheric carbon dioxide threaten rice crops and their nutritional value. Warming oceans in combination with historic overfishing are decreasing fishery productivity in the eastern Pacific.

- Japanese poetry draws inspiration from climate and seasons. The subject matter of haikus, a popular short form of poetry with a 5-7-5 syllable structure, is traditionally nature-themed (examples below). Words revolving around seasons called kigo in Japanese, are commonly found in haikus. Kigo include holidays, weather phenomena, animals, and plants.

Examples of Kigo Haikus

| Author | Japanese Poem | English Translation |

| Matsuo Basho | 閑けさや (Shizukesa ya)

岩にしみいる (Shizukesa ya Iwa ni shimiiru) 蝉の声 (Semi no koe) |

Oh, tranquillity!

Penetrating the very rock A cicada’s voice |

| Yosa Buson | 春の海 (Haruno-umi)

ひねもすのたり (Hinemosu-Notari) のたりかな (Notarikana) |

Spring ocean

Swaying gently All day long |

| Yamaguchi Sodo | 目には青葉 (Me ni wa aoba)

山ほとゝぎす (Yama hototogisu) はつ松魚 (Hatsu gatsuo) |

The green leaves for eyes

The little cuckoo in the mountain The first bonito (fish) of the season |

Language Practice

In progress.

References and additional resources

- Anderson, A. “Learning from Japan: Promoting Education on Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction.” The Brookings Institution. March 2011. https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/learning-from-japan-promoting-education-on-climate-change-and-disaster-risk-reduction/.

- Bernier, A. “An Introduction to the Japanese Language.” Babbel Magazine. July 2021. https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/guide-to-japanese-language.

- Burleson, P. “The History and Artistry of Haiku. Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education. October 1998. https://spice.fsi.stanford.edu/docs/the_history_and_artistry_of_haiku.

- Case, M. Tidwell, A. “Climate impacts threating Japan today and tomorrow.” World Wildlife Fund. 2008. https://www.wwf.or.jp/activities/lib/pdf_climate/environment/WWF_NipponChanges_lores.pdf.

- “Climate Change Communication and Education.” Monitoring and Evaluating Climate Communication and Education Project. October 2022. https://education-profiles.org/eastern-and-south-eastern-asia/japan/~climate-change-communication-and-education.

- Deltaworks. “Japan, Kumamoto, Minamioguni.” Pixabay. November 2015. https://pixabay.com/photos/japan-kumamoto-minamioguni-canyon-1040668/.

- “Disaster Preparedness Walk” AC Japan Video Information https://www.ad-c.or.jp/campaign/search/index.php?id=792&sort=businessyear_default.

- Francisco, A. “Japan’s Three Climates.” TOFUGU. October 2014. https://www.tofugu.com/japan/japan-climate/.

- Gerretsen, I. “Earth’s fish are disappearing because of climate change, study says.” CNN World. February 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/28/world/climate-change-fishing-oceans-global-warming-intl/index.html.

- Hans. “Pink petaled flowers.” Pixabay. March 2019. https://pixabay.com/photos/pink-cherry-blossoms-flowers-branch-324175/.

- “How the climate crisis impacts Japan.” The Climate Reality Project. August 2019. https://www.climaterealityproject.org/blog/how-climate-crisis-impacts-japan.

- Johnston, E. “Environment education that connects all the dots.” The Japan Times. January 2023. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/01/17/national/environment-education-schools/.

- Jozuka, E. “Japan’s Sapporo Snow Festival had to import its snow this year.” CNN Travel. February 2020. https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/japan-sapporo-snow-sculpture-festival-climate-crisis-hnk-intl/index.html.

- Nogi, K. “Japan’s 2011 tsunami, then and now – in pictures.” The Guardian. March 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/10/japans-2011-tsunami-then-and-now-in-pictures.

- “Nymphoides peltata.” Flower Database. 2023. https://www.flower-db.com/en/flowers/nymphoides-peltata.

- Pollmann, M. “4 Years Later, What Japan Can Teach the World About Disaster Preparedness” The Diplomat. March 2015. https://thediplomat.com/2015/03/4-years-later-what-japan-can-teach-the-world-about-disaster-preparedness/.

- Regan, H. “Human-induced climate crisis is making Japan’s cherry blossoms bloom earlier.” CNN Travel. May 2022. https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/climate-crisis-cherry-blossom-kyoto-japan-intl-hnk-scn/index.html.

- “Season Word List: The Yuki Teikei Haiku Season Word List.” Yuki Teikei Haiku Society. 2019. https://yukiteikei.wordpress.com/season-word-list/.

- Sugimura, M. “Education for sustainable development and the role of UNESCO associated schools: the case of Japan.” The HEAD Foundation. June 2023. https://digest.headfoundation.org/2023/06/15/education-for-sustainable-development-and-the-role-of-unesco-associated-schools-the-case-of-japan/.

- “Ten well-known Japanese haiku poems.” Masterpieces of Japanese Culture. n.d. https://www.masterpiece-of-japanese-culture.com/literatures-and-poems/most-famous-10-haiku-poems-in-japanese-and-english.

- Varga, G. “Autumn Leaves (Koyo) In Japan 2023 – Fall Colours Forecast and Viewing.” You Could Travel. May 2023. https://www.youcouldtravel.com/travel-blog/autumn-leaves-festival-koyo-japan-2023#What-is-Ky-Matsuri-or-Autumn-Leaves-Festival.

- Watanabe, A. Toyoda, T. Notehelfer, F. “Japan.” Encyclopedia Britannica. June 2023. https://www.britannica.com/place/Japan.

- “Yamayaki Mountain Burning Festival Mount Omuro.” Japan Experience. March 2018. https://www.japan-experience.com/all-about-japan/shizuoka/events-festivals/omuro-yamayaki.