How is this related to climate?

- A glacier is a large mass of snow and ice that has accumulated over many years and is present year-round.

- Glaciers naturally flow downhill. At high elevations, they accumulate mass as snow is added and becomes compressed into ice. At low elevations, they lose mass due to melting or calving. If the mass added is greater than the mass lost, the glacier advances. If the mass lost is greater than the mass added, the glacier retreats.

- On average, glaciers worldwide have been retreating since at least the 1970s and the rate at which they are doing so has accelerated since the early 2000s. This is because increasing average temperatures are melting more ice and precipitation tends to fall more as rain than snow.

- Retreating glaciers will have substantial social and ecological impacts around the world.

- Glaciers store more water than all of the lakes, rivers and atmosphere combined and provide freshwater for communities and ecosystems.

- Land and sea ice are habitats for many species.

- Melting glaciers will cause sea level rise and flooding in coastal and low-lying areas.

- The area of Earth’s surface that glaciers cover, which is currently about 10%, plays a role in temperature regulation. When solar radiation hits Earth, the amount reflected back into space, known as albedo, depends on the color of the surface it hits. Ice reflects nearly all solar radiation because it is white, while the dark-colored ocean absorbs almost all solar radiation. As ice melts, the area of Earth’s surface that is white decreases and the area that is dark increases, absorbing more solar radiation. This raises temperatures more, causing more ice to melt and setting up a positive feedback loop known as the ice-albedo effect.

- Glaciers are key indicators of both present and past climate changes.

- Glaciers are sensitive to temperature and precipitation, so any changes to these climatic conditions can be seen in the shape and size of glaciers. Small glaciers tend to respond more quickly to climate changes than large ones.

- As glaciers form and grow, climate markers are embedded in the layers of ice. For example, air bubbles in the ice contain the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration at the time the layer was formed. The ratio of oxygen isotopes present in the ice crystals can reveal what percentage of surface water was frozen and what percentage was liquid at the time they were formed.

- As they retreat, glaciers leave behind characteristic landforms and other features, which scientists can use, along with their locations and ages, to determine which regions of the world had climate conditions suitable for glaciers and when. Some of these features include:

- U-shaped valleys

- Striations – scratches made by rocks embedded in ice

- Glacial till – sediment of various size and composition transported by ice

- Drumlins and moraines – hills and ridges, respectively, made of glacial till

- Glacial erratics – large rock boulders transported by glaciers

- In addition to being the subject of much scientific study, glaciers have captivated artists since at least the 17th century. In the 19th century, scientists and artists commonly worked together to document glaciers. Watercolor paintings in particular have a strong history of depicting glacial landscapes. Below are just some examples of artwork focusing on glaciers.

Examples of Glaciers in Art

John Ruskin, British, 1819–1900. Mer de Glace-Moonlight, 1863. Watercolor. ALPINE CLUB PHOTO LIBRARY.

- John Ruskin, a 19th century artist, naturalist and art critic known for taking some of the first alpine photographs, spent much of his time in the French Alps, in awe of the mountains and their glaciers.

- In this painting, he depicts the Mer de Glace, a valley glacier located on Mont Blanc. The glacier wraps around the side of the mountain in the lower right corner. The mountain itself has a mysterious, haunting quality, reflecting Ruskin’s reverence for it.

- Ruskin uses the style of Joseph Mallard William Turner, an English Romantic landscape painter known for his studies of light, color and the atmosphere. This painting is just one example of the many watercolors done to document glaciers, both for scientific and artistic purposes, in the 1800s.

Francois-Auguste Biard, French, 1799–1882. Pêche au morse par des Gröenlandais, vue de l’Océan Glacial (Greenlanders Hunting Walrus: View of the Polar Sea), 1841. Oil on canvas. MUSÉE DU CHATEAU.

- Under King Louis Philippe’s rule from 1830 to 1848, the French government invited artists to participate in Arctic exploration voyages. Francois-Auguste Biard, one of the king’s favorite artists, joined the Arctic leg of the 1838-1840 expedition. The painting above, which was exhibited at the 1841 Paris Salon, was a result of this expedition.

- The Arctic freed Biard from the traditional conceptions of landscape painting and inspired him to mix fact and fantasy, naturalism and romanticism in this work. The sea ice is massive and takes on many jagged, abstract and unnatural shapes, reflecting the hallucinatory effects Biard felt it had on him. On the other hand, he does accurately portray the gray sky and the blue-green tints of ice.

- The painting also comments on human survival in harsh, little-known environments. In the foreground, Indigenous Peoples hunt walrus in kayaks amid the ice, based on sketches Biard made during the voyage.

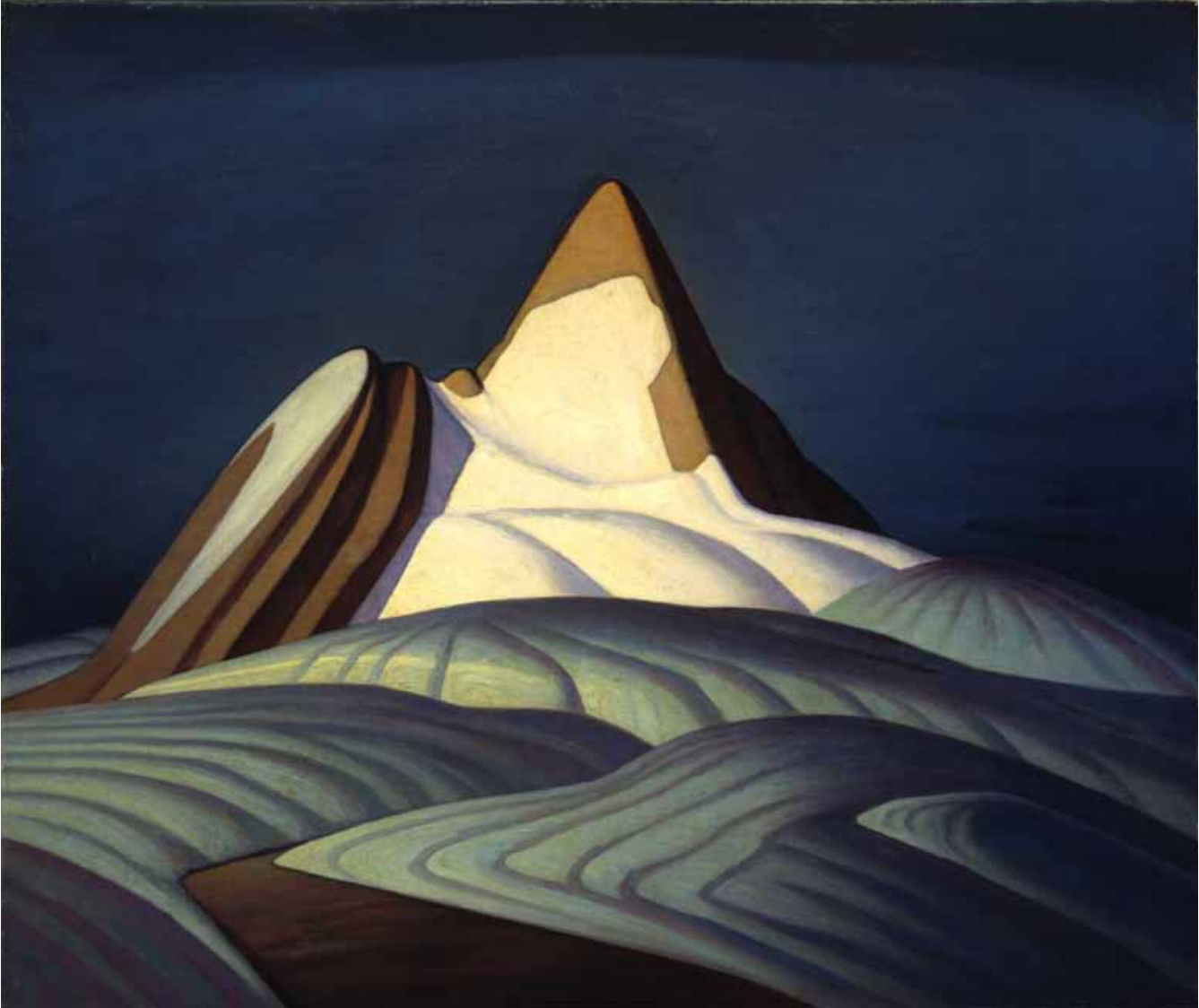

Lawren Harris, Canadian, 1885–1970. Isolation Peak, Rocky Mountains, 1930. Oil on canvas. Purchased by the Art Committee with income from the Harold and Murray Wong Memorial Fund, 1946. HART HOUSE PERMANENT COLLECTION UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO.

- This painting of Mont des Poilus in Yoho National Park in Alberta Canada is characteristic of artist Lawren Harris.

- As a member of the Canadian Group of Seven, a group of landscape painters, he often painted alpine and polar landscapes.

- Harris tried to create a Canadian style of painting different from that of Europe, often using simple forms, large areas of colors and geometric shapes, similar to modern art. The mountain peak is a simple triangle, a realistic depiction of a glacial horn. The light-colored ice and thin dark stripes representing moraines flow toward the viewer in geometric shapes.

- Harris was very spiritual and his beliefs led him to reduce forms and colors to their most basic elements. He also believed that the north was a source of cosmic power and often remarked on the cool, clear northern light. The lack of visible light source casting a warm glow on the face of the mountain and the sky that is free of clouds reflect these views and create a surreal, otherworldly image.

Arthur Oliver Wheeler, Canadian, 1860–1945. Athabasca Glacier, Jasper National Park, 1917. Black and white photograph. NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF CANADA. |

Gary Braasch, American, 1950–2016. Athabasca Glacier, Jasper National Park, 2005. Archival inkjet print. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST. |

- In 2005, Gary Braasch, artist, naturalist and explorer, took a photo of the Athabasca Glacier in Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada (above right). He compared it to a photo taken by Irish-Canadian land surveyor Arthur Oliver Wheeler in 1917 (above left).

- Together the photos confirm that by 2005, the Athabasca Glacier had lost half of its volume and retreated almost a mile since it was first described in 1898. This is most clearly evidenced by the ice flowing down the valley on the left side of both photos. In Wheeler’s photo, the ice fills the valley and reaches the foreground of the image, but in Braasch’s, it is substantially smaller, only filling half of the valley. Braasch’s photo also shows significantly less ice in the smaller valley to the right.

- Similar comparisons between historical lithographs and present-day images depicting alpine glaciers provide information about reducing size and extent of glaciers due to global warming.

Camille Seaman, Shinnecock Tribe, 1969–. Grand Pinnacle Iceberg, East Greenland, 2006. Ultrachrome archival inkjet print. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND RICHARD HELLER GALLERY.

- In the 17th century, many explorers shared the belief that there was a temperate ocean free of ice around the North Pole. This theory, which encouraged Arctic exploration and inspired fictional stories, including Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Jules Verne’s The Adventures of Captain Hatteras, was known as the Open Polar Sea.

- It now appears that the Open Polar Sea may become a reality. As the Arctic warms twice as fast as the rest of the world, sea ice that normally stays frozen year-round is melting away. In fact, 44% of the Arctic’s summer sea ice has melted since 1979.

- This photograph by Camille Seaman captures this idea. By focusing on a single dissolving iceberg, she makes it seem isolated, alone and vulnerable. Also, by dramatically contrasting the bright white of the iceberg in the foreground with the dark background, she creates a forlorn and somber mood.

Chris Jordan, American, 1963–. Denali Denial, 2006. Archival inkjet print. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST. |

Ansel Adams, American, 1902–1984. Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake, Denali National Park and Preserve, Alaska, 1947. Gelatin silver print. THE CENTER FOR CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA LIBRARIES. |

- Chris Jordan’s digitally-created image titled Denali Denial (above left) was inspired by a photograph taken by Ansel Adams in 1947 of Mount McKinley in Denali National Park and Preserve in Talkeetna, Alaska, USA (above right).

- Adams was an American landscape photographer and environmentalist famous for his black and white photographs of the western United States. To him, Alaska represented the quintessential wilderness and Mount Denali represented Earth’s sovereignty.

- At 20,000 feet (6,096 meters), Mount Denali, also known as Mount McKinley, is the tallest mountain in North America. It has five glaciers.

- In Jordan’s image, Adams’ photo is reconstructed using 24,000 General Motors Company (GMC) Yukon Denali SUV logos of varying shades of gray, white and black (close up below).

A close up of the individual GMC Yukon Denali SUV logos that make up Jordan’s Denali Denial.

-

- 24,000 is the number of GMC Yukon Denali SUVs sold during a six-week period in 2004.

- In half of the logos, the word “Denali” is changed to “denial.” Jordan wanted to point out the irony of a low-mileage SUV that requires a lot of gasoline and contributes to climate change being named after a mountain that represents the pristine wilderness. The use of the word “denial” also suggests that society is in denial about climate change while continuing to buy personal cars and engage in other consumerist practices.

Xavier Cortada, American, 1964–. Astrid, 2007. Sea ice from Antarctica’s Ross Sea, sediment from the Dry Valleys, and mixed media on paper. Gift of the artist and Juan Carlos Espinosa. WHATCOM MUSEUM.

- Xavier Cortada physically incorporates elements of glaciers into his artwork. In the painting above, he uses ice and sediment from the Ross Sea and Dry Valleys of southern Antarctica. To create it, he applied a layer of paint to the paper, and covered it with sediment. Using ice as a brush, he worked the sediment and paint mixture into the paper. Then he repeated this process to make several different layers.

- This painting is abstract but Cortada believes it embodies Antarctica and the movement of ice. It is named after the Princess Astrid Coast in eastern Antarctica, another nod to the frozen continent.

Alexis Rockman, American, 1962–. Adelies, 2008. Oil on wood. THE COLLECTION OF ROBIN AND STEVEN ARNOLD.

- Alexis Rockman’s Adelies speaks primarily to two aspects of Antarctic life that are being threatened by a changing climate: Adelie penguins and sea ice.

- In the painting, a group of Adelie penguins congregate at the edge of a towering iceberg. The iceberg is drifting in isolation, without sight of the mainland or other icebergs. Together these two artistic choices convey the precarious situation that these penguins are in. Their feeding depends on sea ice, which is rapidly melting away. The penguins in the painting are on the edge of an iceberg, in danger of falling off, like penguins in Antarctica are on the edge of disaster, potentially in danger of dwindling populations or extinction.

- The majority of the painting is taken up by a massive iceberg that is floating alone in the middle of the ocean. This is a reference to calving occurring on the Antarctic ice shelf. Calving is when a mass of ice splits off from a larger mass of ice or glacier. This process is becoming increasingly more common in the Arctic and Antarctic as icebergs and glaciers melt and become more unstable. For example, an iceberg about 20 times the size of Manhattan, New York, USA broke away from the Brunt Ice Shelf in the Weddell Sea in February 2021.

Jyoti Duwadi, American, 1947–. Red Earth-Vanishing Ice, 2008. Mixed-media. SUNDARAM TAGORE GALLERY.

- Red Earth-Vanishing Ice is a site-specific installation at the Sundaram Tagore Gallery in New York, NY, USA with several different elements:

- A block of ice is suspended from a pipe in the gallery’s ceiling. The pipe is wrapped in yak-hair rope. Everyday, the ice is replenished and left to melt onto a rock from the Narmada River in India.

- Surrounding the ice are several handmade wooden containers, copper cauldrons and brass vessels containing water from New York and Kathmandu, Nepal, Duwadi’s birthplace. Flowers float on top of the water.

- A 15-foot canvas is draped behind the containers and block of ice. The canvas is painted with turmeric, earth pigments and Guggul, an herbal preparation made from the gum of myrrh trees, to represent the regenerative powers of nature.

- The installation as a whole symbolizes the purity and scarcity of freshwater and the melting of glaciers around the world.

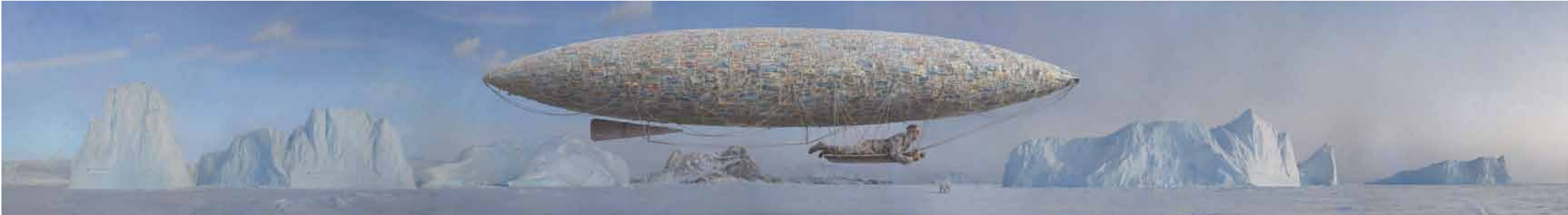

Nicholas Kahn and Richard Selesnick, British and American, 1964– and 1964–. Currency Balloon, 2008. Archival pigment print. YANCEY RICHARDSON GALLERY.

- Currency Balloon by Nicholas Kahn and Richard Selesnick was part of a 2008 installation called Eisbergfreistadt (Iceberg Free-State) by the two artists.

- In the installation, Kahn and Selesnick create a historical fiction narrative set in 1923 Germany, or the Weimar Republic, as it was called then. A massive iceberg from Spitsbergen, an island in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, has run aground on the shores of Lubeck in northern Germany.

- The iceberg becomes a site for trading and banking, alluding to the idea that Arctic resources are exploited for economic gain.

- In the narrative, scientists believe that the iceberg broke away from an Arctic glacier because heat from factory smoke caused increased breakup of the ice pack. This directly links the burning of fossil fuels, beginning in the Industrial Revolution, to modern climate change.

- The fake banknotes in the installation read “To burn oil from Azerbaijan to Tibet puts the world on fire” and depict images of factories spewing smoke, further connecting industrialization to climate change.

- In the installation, Kahn and Selesnick create a historical fiction narrative set in 1923 Germany, or the Weimar Republic, as it was called then. A massive iceberg from Spitsbergen, an island in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, has run aground on the shores of Lubeck in northern Germany.

- In this image, a man scouts the Arctic landscape in a blimp that is plastered with real and fictional banknotes from German city states. In doing so, the artists critique the connection between greed, consumerism and materialism and climate change. It is these factors that drive people to exploit the last regions of untouched wilderness around the world.

- A single polar bear stands on the ice underneath the man’s head. It is turned away from the viewer, illustrating it as meek, shy and isolated, rather than a ferocious predator. This alludes to its status as an endangered species.

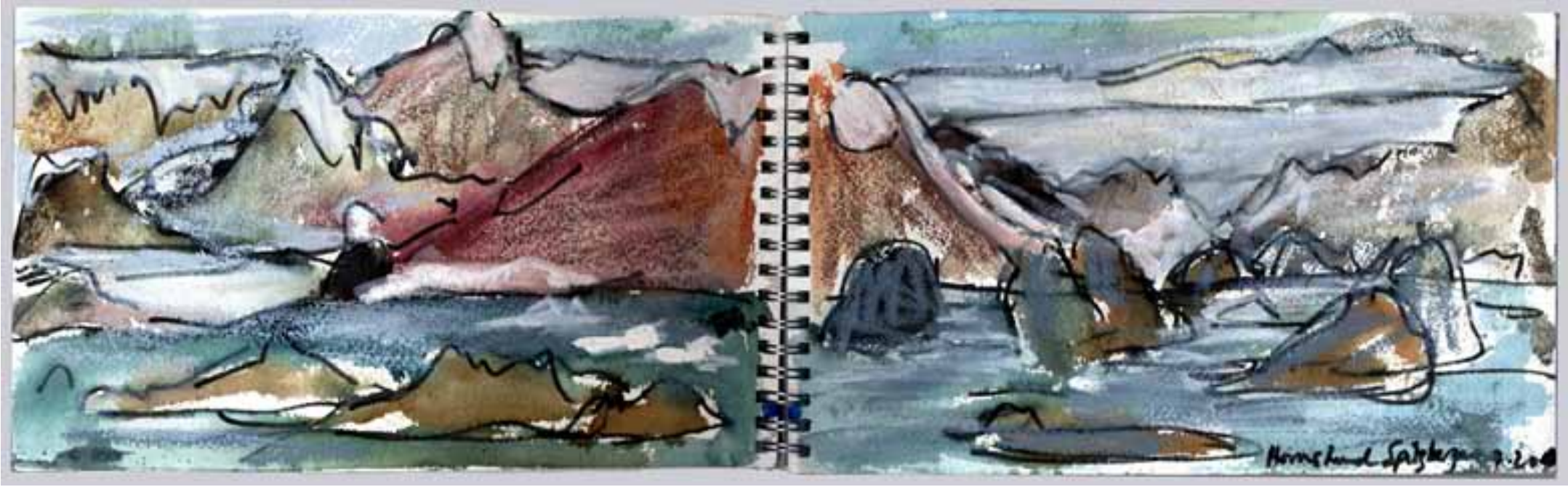

Nerys Levy, American, 1945–. Arctic Sketchbook, Hornsund, Spitsbergen, Norway, 2009. Watercolor and water soluble ink. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST.

- Similar to Biard, Nerys Levy uses watercolor and ink to document the polar landscape of the Arctic in this quickly-drawn study. Among depictions of glacial landscapes, this one stands out for its bright, warm colors; Levy paints with reds and browns in addition to cool blues, grays and white commonly used to portray ice.

- Levy’s personal concerns about climate change have compelled her to explore and document the Earth’s poles.

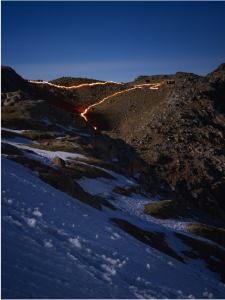

Simon Norfolk, British, 1963–. The Lewis Glacier, Mt. Kenya, 1934, 2014. Photograph. |

Simon Norfolk, British, 1963–. The Lewis Glacier, Mt. Kenya, 1934, 2014. Photograph. |

Simon Norfolk, British, 1963–. The Lewis Glacier, Mt. Kenya, 1963, 2014. Photograph. |

Simon Norfolk, British, 1963–. The Lewis Glacier, Mt. Kenya, 1963, 2014. Photograph. |

Simon Norfolk, British, 1963–. The Lewis Glacier, Mt. Kenya, 1983, 2014. Photograph. |

Simon Norfolk, British, 1963–. The Lewis Glacier, Mt. Kenya, 2004, 2014. Photograph. |

- Together, these six photographs constitute the series “When I am Laid in Earth” by British photographer Simon Norfolk, which chronicles the retreat of the glacier on Mt. Kenya in Kirinyaga, Kenya.

- Using historical maps and modern GPS surveys, Norfolk reconstructed the shape of the glacier in 1934, 1963, 1983 and 2004. He then marked the extent of the glacier in these years with a line of fire and photographed the landscape using long, slow exposures.

- The years were chosen somewhat arbitrarily; the only one with significance is 1963, which is when Norfolk was born.

- The fires burn petroleum, which Norfolk uses to inject additional meaning into the series. Much of today’s global warming, which is causing glaciers to melt, is a result of the burning of fossil fuels, such as petroleum. The gap or distance between the ice and the fire in Norfolk’s photographs represents the extent of glacier melting.

- Norfolk uses fire as a means of “awakening” the volcano. Mt. Kenya is a long-dead, barren, eroded megavolcano, but the fire in the photographs looks like lava. Norfolk imagined that if the volcano could speak, it would have angry, lava-like words for what humans had done to its glacier.

- Mt. Kenya was chosen for this project for several reasons. First, it has been precisely mapped since the 1930s, so it was relatively easy to determine the size of the glacier at various times. Also, the glacier is very clean and bright and overlies dark rock, so it is easily visible in photographs.

- The series won a Sony World Photography Award in 2015.

|

|

Richard Mosse, Irish, 1980–. Ice Cave, Vatnajökull, 2014. Photograph.Richard Mosse, a conceptual documentary photographer, used a large-format plate-film camera and infrared film to photograph the ice cave under the Vatnajökull Glacier in Iceland. Ice caves form when warm air enters where water flows beneath a glacier, causing melting. The smooth curves of the ice and jagged icicles, the use of infrared film and blue tinge applied to the prints create a surreal scene that resembles a sci-fi landscape.

|

|

Blane de St. Croix, American. Dead Ice, 2014. Mixed media, aqua resin, eco epoxy, and recycled material.This piece, which is a hybrid between sculpture and painting, explores the conflict between humans and the environment. More than twice as long as it is tall, it captures the idea of landscape that usually belongs to paintings. It was made by painting, layering and sanding ecologically-friendly and recycled materials. There are two physical sides to the work: one human (above left) and one natural (above right), with the sculpture itself representing a border between them.

-

- The human side is a fragmented vessel, an artifact from failed Arctic explorations.

- The natural side is an interpretation of Arctic dead ice, which refers to ice shed by a glacier into the ocean, where it ultimately thaws.

- The two sides negatively impact one another. Human exploration, and human society in general, has disrupted Arctic sea ice, glaciers and ecosystems. Arctic sea ice has made it difficult for humans to explore the northern reaches of the globe and has resulted in the loss of many lives.

Noemie Goudal, French, 1984–. Glacier 1, 2016. Photographs printed on biodegradable paper and mounted on plastic canvas with biodegradable glue.

- Noemie Goudal, a French conceptual artist, has a particular interest in the blending and clashing of artificial and natural images. She took several steps to do so in her work on the Rhône Glacier in southern Switzerland:

- First she photographed the glacier.

- Then she printed the photos on 3.5-meter-tall sheets of biodegradable paper, which she mounted on a plastic canvas with biodegradable glue.

- Finally, she suspended the canvas in front of the location that she had photographed and, throughout a single day, photographed the prints in front of the landscape until they had completely disintegrated.

- By photographing the prints in the many stages of disintegrating, this piece speaks to the continuous changes a landscape undergoes. Also, the disintegration of the prints over a single day alludes to the fragility of glacial ecosystems.

Blane de St. Croix, American. Dark/Light Arctic Ice Float, 2020. Recycled foam, wooden panels, acrylic paint, water-based pigments, glue, eco resin, cellophane sheets and vinyl paste. MASSACHUSETTS MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART.

- This sculpture captures the enormity of icebergs by juxtaposing the portion that is above water and the portion that is underwater. The iceberg is mounted on a wooden shipping crate. The above-water portion is sitting on top of the crate, not surrounded by anything, and is bright white. In contrast, the underwater portion is inside the crate, blue-black in color and surrounded on three sides by wooden panels that are painted to match the iceberg.

References and additional resources

- “Albedo and Climate.” UCAR Center for Science Education. 2014. https://scied.ucar.edu/learning-zone/how-climate-works/albedo-and-climate.

- “Ansel Adams.” Wikipedia. 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ansel_Adams.

- “Climate Change Indicators: Glaciers.” United States Environmental Protection Agency. n.d. https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-glaciers.

- “Dark/Light Arctic Ice Float (2020).” Blane de St. Croix. n.d. https://blanedestcroix.com/2020/11/20/dark-light-arctic-ice-float/.

- “Dead Ice (2014).” Blane de St. Croix. n.d. https://blanedestcroix.com/2014/05/07/dead-ice/.

- Freedman, A. “Iceberg Larger Than New York City Breaks Off the Brunt Ice Shelf in Antarctica.” 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2021/02/26/iceberg-calves-antarctica-brunt-ice-shelf/.

- Gambino, M. “Art Chronicles Glaciers As They Disappear.” Smithsonian. 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/art-chronicles-glaciers-as-they-disappear-180947859/.

- “Glaciers and Climate Change.” National Park Service. 2018. https://www.nps.gov/articles/glaciersandclimatechange.htm.

- “Glaciers and Glacial Landforms.” National Park Service. n.d. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/geology/glacial-landforms.htm.

- “Glaciers and Past Climates.” National Park Service. 2018. https://www.nps.gov/articles/glaciersandpastclimates.htm?utm_source=article&utm_medium=website&utm_campaign=experience_more&utm_content=small.

- “Kahn & Selesnick: Eisbergfreistadt.” Washington City Paper. 2007. https://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/298463/kahn-selesnick-eisbergfreistadt/.

- Matilsky, B. Vanishing Ice: Alpine and Polar Landscapes in Art, 1775-2012. Bellingham, Whatcom Museum, 2013.

- “Meltdown – Now Open.” Project Pressure. 2019. https://www.project-pressure.org/meltdown-now-open/.

- O’Hagan, S. “Meltdown: Chilling Proof of Global Heating.” The Guardian. 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/nov/10/meltdown-visualizing-climate-change-project-pressure-glaciers-photography.

- Reyes, B. “Glaciers and Climate Change.” The EPA Blog. 2009. https://blog.epa.gov/2009/09/10/glaciers-and-climate-change/.

- Strecker, A. “When I Am Laid in Earth: Mapping with a Pyrograph.” LensCulture. 2016. https://www.lensculture.com/articles/simon-norfolk-when-i-am-laid-in-earth-mapping-with-a-pyrograph#slideshow.

- “The Group of Seven.” n.d. The Group of Seven. https://thegroupofseven.ca/.

- “When I am Laid in Earth.” Simon Norfolk. n.d. https://www.simonnorfolk.com/when-i-am-laid-in-earth.